Silence of the lass

Sexual harassment in India is very much a living and breathing entity that hides behind the lack of justice.

Shame has a tormenting nature. It shakes one’s foundation, questions beliefs, makes one hide from the vicious and pernicious gaze of onlookers. The recent case of Doctor Larry Nassar, the former USA gymnastics team doctor whose years of sexual abuse was hidden until the brave and agonising testimonies of 160 victims who overcame the shame and repercussions of disclosure and spoke up, sent shock waves across the globe. This comes at a time when the “me-too” debate has brought out harsh truths and harassment across the West to put paid to years of silence, abuse, harassment and mental anguish. However vocal and vociferous the debate may be, Indian hubris still shirks from the pain of revelation, ducking behind a cloak of apprehension, fear and rebuke. This was apparent with Sheryl Sandberg’s warning, “Calling out men could result in a backlash! For so many years everyone kept quiet, and women faced the brunt as sexual exploitation grew in leaps and bounds and women began to believe men will be men, basically perverts! We began to normalise weird behaviour by not shouting out each time! Even Facebook has begun banning women who call me scum and thrash! This is a battle that needs to be seen to its bitter end if the future belongs to women!

We need to make the world a safer place for our girls,” she has said (in reports). Deep under the pain and humiliation lies an irrevocable realisation that courageous voices are squashed due to recrimination and a society that is quick to ostracise. We are in grave danger of losing faith, credibility and truth-seeking as the metoo campaign has not awakened those silent voices to action as calling out perpetrators in our country is faint at best, and non-existent as a rule. Columnist Shobhaa De has written an honest column for this article (complete column on far right), where she says, “Nobody wants to address the elephant in the room, which is that women have had to put up with sexual harassment in the workplace for decades. Shut up and put up. They have done so out of fear. Fear of losing their jobs, their livelihoods, their dignity. Those who have gutsily called out their tormentors have found themselves isolated and ostracised — even by other women.”

But voices that have the fortitude to come out need the support of the judiciary, and therein lies the paradox which Supreme Court lawyer Saurabh Kirpal has succinctly addressed, “Sexual harassment has not been a priority for us. The Supreme Court laid down the Vishakha guidelines on sexual harassment in 1997. In the judgment they directed that the guidelines would be in force till parliament enacted a law in this regard. But it took parliament 16 years to finally enact a law in 2013. This delay is a symptom of the fact that true workplace equality, even though it is embodied in the Directive Principles of State Police in our Constitution, is not a matter of urgency or priority for the authorities.”

Sreemoyee Piu Kundu

Sreemoyee Piu Kundu

A staunch women’s activist and bestselling author, Sreemoyee Piu Kundu has seen abuse and harassment closely with her new book Status Single, where she interviewed 3,000 women. She reveals, “Like in other parts of the world, sexual harassment at work is a serious offence. But a survey by the Indian National Bar Association that was carried out in 2017 revealed that of the 6,047 participants (both men and women), 38 per cent faced harassment at work and of these 69 per cent chose silence. Apart from the fear of losing their jobs and a lifelong cursed stigma, there is the looming reality of long winding legal procedures, and in a country where rapists are let loose and ministers and businessmen involved in multi-crore scams go scot free, a woman’s shrill voice is seldom heard or given the respect it deserves.”

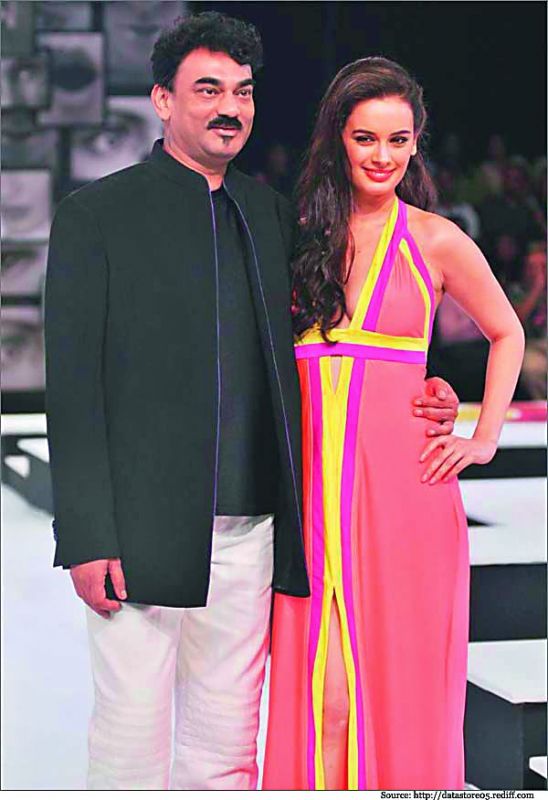

Designer Wendell Rodricks with a model

Designer Wendell Rodricks with a model

Sexual harassment in India is very much a living and breathing entity that hides behind the lack of justice. Corporate India does have anti-sexual harassment committees but sees a misuse of it, while other industries do not have a formal body for such complaints, or are there merely in name. Designer Wendell Rodricks believes that it is prevalent in all industries, he feels, “If anyone finds the courage to speak up, the legal system wrings out any sense of justice because of the long drawn battle. The metoo campaign is good for both men and women. When fashion photographers Mario Testino and Bruce Weber were accused by male models of sexual exploitation, it just reiterated the fact that it is prevalent in all industries. But if we pause, and understand the issue for what it is in India, it’s terribly grave. The reality is that it is extremely difficult for a person to come out in the open against an abuser. For him or her, it means living with the shame for decades (especially in the Indian context). The shame does not go away unless there is a legal mechanism that sees justice prevail, and a society that apologises. Unfortunately, the judicial system takes too long. But if we see a few cases come to the fore, I do personally feel that there will be ripples in India as well, with more proponents of the metoo campaign, and people will come out and have the strength to voice this abuse. The fact that sexual harassment is happening, not just in the glamour and fashion industry but across corporate, finance and media, needs to be brought out. It is happening in my industry, and some male models strongly believe that if you do not succumb to this power struggle you are at a loss. That you have to sleep with someone to succeed if you want to get ahead, and that needs to be stopped. Sadly, sometimes, I have seen families collude when someone has the fortitude and strength to bring it out in the open, comments like ‘are you sure’, ‘is it an exaggeration’, which said to an individual who has had the resolve to come clean makes it even more difficult and anguishing.”

The reality percolates through a desi sensibility that is wrought with self-doubt, escapism and ignorance (what you don’t know cannot hurt you). There are cases of sexual harassment that have come to the fore, but leave alone a few high profile cases like that of Tarun Tejpal, R.K. Pachauri, David Davidar, Phaneesh Murthy, etc, most such claims are either hidden under a veil of silence by the victim, suppressed by organisations or acknowledged for a staggering fee that buys silence. This is India today, anyone with a conscience would surely cringe. Actress Sumalatha Ambareesh comes from an era when the casting couch was a regular phenomenon, and voicing such views was considered sacrilege, and she too is troubled by this lack of responsibility and accountability, and addresses the pernicious nature that lives and breathes in our social fabric, “If you are asking me specifically about men in the movie industry, I would say certain kind of men exist everywhere, in every workplace, wherever they feel powerful enough. It’s only the famous names which draw attention. Lakhs of working women suffer too, silently. Let me begin with how I started my day, by reading about a teenage actress being molested on a flight, and coming across the terrible news of three girls under six years in different villages raped and one also killed in an unspeakable perverted manner.

Is there any appropriate punishment in our system for sick beasts like these? There is no doubt whatsover that women of every age in every country have been prey, and victims of sexual predators and those men deserve no sympathy. Women have been made to keep quiet, made to feel ashamed just for being the unwilling victims of unwanted attention just because for centuries men have gotten away with sexual harassment of every kind. And it’s always been the victim who is shamed, and never the perpetrator. I think it’s high time, and rightly so, that sexual offenders are named and shamed finally. Maybe this will keep atleast that section of society which has escaped for too long, and is wary of the notoriety involved, in check. However, very unfortunately and horrifically, we still don’t have solutions for the thousands of rapists, paedophiles and hardcore criminals who rape and kill even children, and get away with it.”

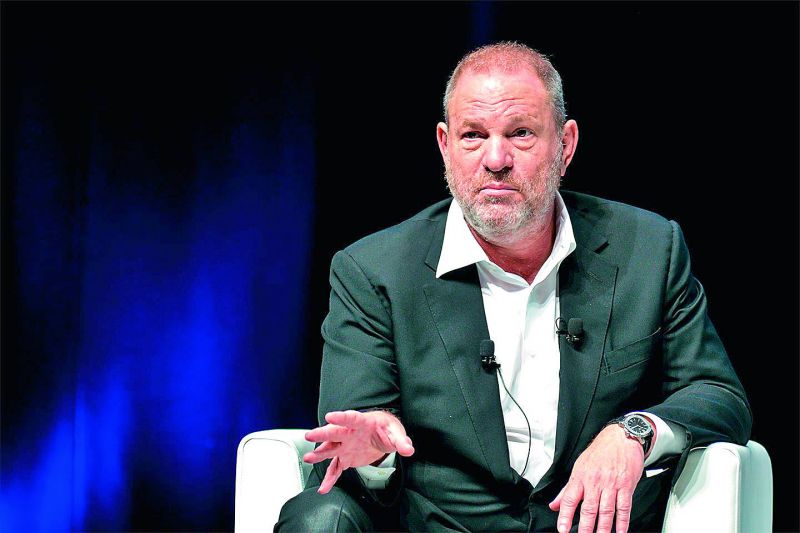

Wendell speaks of the glamour quotient to such revelations, concerned about how we view sexual harassment, “Everybody seems to be looking at the story because of the glamour industry involved, but look at the Tarun Tajpal case, and there are many more hidden, sexual harassment instances across the board. This abuse, this sense of power, is not only a criminal offence, it is a moral sin. And it’s happening everywhere, I personally feel that if someone came up and spoke about it, then it will atleast be a start for others to gather strength to speak up. In my own industry, male models are propositioned and they know if they do not comply, the climb up the ladder will be slow, or none.” While the West has come a long way in acknowledging such behaviour without fear of recrimination, as in the case of Harvey Weinstein, and Larry Nassar’s victims, each of whom spoke of the abuse in scary detail, the Indian dilemma lies in brushing such issues aside. But for how long?

Harvey Weinstein

Harvey Weinstein

While Harvey Weinstein and men like him deserve all the backlash and outrage according to actress Sumalatha, she hopes that innocent men are not targetted in this wave, voicing concerns about such campaigns, “There is always another side to this... the only downside is the chance of misusing a trend to unleash maybe manipulation/blackmail/vendetta that might also occur, especially if it comes to a high-profile person. Unfortunately, opportunists exist in both genders. So how to strike a balance is a million-dollar question. But women have been victimised forever, so this would be an unfortunate fallout and though it’s not ideal, it can’t be helped either. The government should be thinking very, very seriously about changes in law regarding women safety, no compromises should be acceptable. Think about this, not all men are rapists or sexual offenders, but all rapists are men — that’s the sad truth. It’s time we put an end to being victimised. It is time men realise that No means No!”

A senior lawyer who is on the board of various Anti-Sexual Harassment Committees is cautious, “The MeToo campaign is a good movement, and hopefully it would give women the courage to speak up and complain on the right forum. But being on various Anti-Sexual Harassment committees, I’ve also seen numerous frivolous complaints because of relationships going sour, promotions being delayed, etc. and I just hope this movement is not abused by even a few individuals.” A caution that needs to be taken into cognizance. For Gajra Kottary, award-winning screenplay writer and author of Girls Don’t Cry, the ramifications of not acknowledging sexual abuse or harassment can be far reaching. She says, “The warning is real. Since more men than even the best of us can imagine are closet sexual predators, there is a fear psychosis among them that their secrets might be out next, with women being encouraged to speak out. So male employers, in the name of playing safe for their own selves and partly out of bitterness against the female gender that is refusing to dance to their tunes anymore, are now marginalising women in terms of employment. And believe me, in India it’s happening as much if not more in corporate offices too. In rare cases, it’s also true that women are getting even due to personal enmity and crying foul when they haven’t actually been sexually harassed — that’s happening in media and entertainment in India quite a bit. But we have to live and fight all this too, for the solution is certainly not to brush things under the carpet. That is more debilitating for our souls and our identities than a temporary backlash from the men! Above all, we should learn to be the truly fair (as in just) sex, even when the men are not and we have to win the war even if we lose a few battles along the way.”

Gajra Kottary, screenplay writer and author

Gajra Kottary, screenplay writer and author

‘Nobody wants to address the elephant in the room’

A few months ago, much before the Harvey Weinstein issue blew up and blew a few very powerful men apart, I was talking to a very worried senior counsel who told me bluntly his law firm had taken a unanimous decision to stop hiring female interns. He was also thinking of firing a few female full-timers from his prestigious office, because, as he put it, “The risk is simply not worth it!” I asked, “What risk?” And he surprised me by being totally upfront. “I want to focus my energies on representing my clients to the best of my abilities. I don’t want to be stressed out thinking about some girl who imagines I am making a pass at her. I tell you, today’s women are like sharks! They wait for an opportunity and go for your jugular. From a harmless office flirtation, they concoct a rape narrative! And we get screwed — without actually screwing them!” Crude. But blunt and to the point. He is not alone.

Many employers are taking this route because it is easier. Nobody wants to address the elephant in the room, which is that women have had to put up with sexual harassment in the workplace for decades. Shut up and put up. They have done so out of fear. Fear of losing their jobs, their livelihoods, their dignity. Those who have gutsily called out their tormentors have found themselves isolated and ostracised — even by other women. Men in power have told some of these women that they are entirely dispensable. “One female ass is as good as the other. Do you really think we care or notice?”

Harsh words. But they accurately describe the widespread contempt and loathing women endure, while trying to make a life for themselves. A man does not have to be as loathsome as Weinstein. He can exert an equal amount of coercion. That’s where I have a few issues with the global #metoo campaign. It’s one thing to publicly admit you have suffered exploitation, indignity and worse. It is another to expect change. Of course, change will come! I have no doubt about that. It is the interim that’s going to cost women a great deal. Every major transition encounters roadblocks that appear insurmountable. It is only when men start losing their jobs and suffering financial loss that attitudes will realign. In India, this will take longer still. A man who gets publicly stripped becomes a highly dangerous foe. He can go to any extreme to fix the victim. Despite this grim and highly pessimistic scenario, now that the genie is out of the bottle, there is no stopping the juggernaut. If one generation of women is forced to pay the price for their outspokenness, so be it. In the longer run, it will lead to a far more transparent system of working as equals, without having to constantly watch where those eyes and hands and words are travelling.

Vishaka guidelines, 1997:

The Supreme Court passed the landmark Vishaka judgement that defines sexual harassment at the workplace. Among the diktat is “Physical contact and advances; a demand or request for sexual favours; sexually coloured remarks; showing pornography; and any other unwelcome physical verbal or non-verbal conduct of sexual nature.”

Saurabh Kirpal, Supreme Court lawyer

Saurabh Kirpal, Supreme Court lawyer

The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace

(Prevention, Prohibition, and Redressal) Act was a landmark judgement. In April 2013, a reaction to the Nirbhaya rape, where the Parliament passed India’s first law against sexual harassment at the workplace giving the above guidelines a legislative brief and also extended the definition beyond the Vishaka guidelines to “the presence or occurrence of circumstances of implied or explicit promise of preferential treatment in employment, threat of detrimental treatment in employment, threat about present or future employment, interference with work or creating an intimidating or offensive or hostile work environment, or humiliating treatment likely to affect the lady employee’s health or safety could also amount to sexual harassment”.