The echoes of the mountains

Tired of corporate drudgery, author Sohini Sen decided to travel to the Himalayas to not just explore the mountains but also herself.

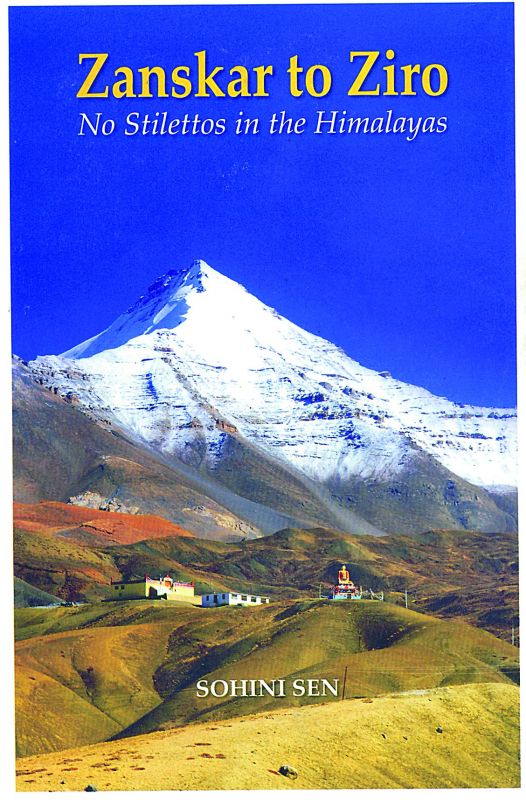

Ever wondered what it would be like to leave everything and explore the unknown lands? To be able to travel to places you have been dreaming of since your childhood? Famous writer Mark Twain once said, “Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all of one’s lifetime.” And so, to not just explore the mountains, but also herself, author Sohini Sen dragged herself out of her regular job, and decided to travel to the Himalayas. Her latest book Zanskar to Ziro: No Stilettos in the Himalayas allows the readers a peep into the adventurous and thrilling world surrounding Asia’s longest mountain range.

Zanskar to Ziro: No Stilettos in the Himalayas by Sohini Sen Rs 995, pp 436 Niyogi Books

Zanskar to Ziro: No Stilettos in the Himalayas by Sohini Sen Rs 995, pp 436 Niyogi Books

“For me, every journey outdoors has meant a self-discovery. It meant travelling down the labyrinthine maze of my mind — piled high with the debris of social norms, the dos and don’ts from my childhood and the never-ending pursuit of goals. There, in those secret, silent corridors, I have finally learned to listen to my soul,” says Sohini, while talking about her travels. But travelling was not always this easy for Sohini, in fact, as a kid she rarely travelled. She reveals that the world of words was her refuge back then. “I was an extremely sick child, who spent a lot of her childhood in bed. My family rarely travelled. You could say I was the female version of the boy Amal in Rabindranath Tagore’s Post Office. So, books were both my window to the world and my magic carpet,” she says.

Young Bhutanese Nun

Young Bhutanese Nun

Travelling didn’t just change Sohini’s perspective of life, but gave it a new meaning. She confesses, “When I did start travelling to the Himalayas, I was in my 40s, and completely sucked into the corporate drudgery of an IT company. The snow-covered pristine mountains changed my outlook of life and set things in perspective.” After travelling 10,000 kilometres through six Indian states and two neighbouring countries (from Jammu and Kashmir in the west to Arunachal Pradesh in the east, Nepal and Bhutan), she says that she is still under the magical spell of the mountains. So, what prompted Sohini to write the book? She quips, “For someone who has, for most of her life, thrived like a parasite on other people’s experiences and writing, it would have been a sin not to pay back in kind. Thus, this book — to share the stillness of the mountains, and the chaos of the quaint village festivals; the oral narratives that change and grow with every retelling; the sense of peace and the sense of danger; the laughter and the pain.”

Paragliding near Pokhara, Nepal

Paragliding near Pokhara, Nepal

Born of the tumultuous union of two vast land masses, and one of the youngest ranges in the world, the Himalayas might be violent at times and unpredictable always. The author shares that she had her fair share of difficulties. “We have often been frightfully cold, seriously unwell, or just plain, awfully dehydrated and hungry. But every time we retired to the plains to lick our wounds, we realised how happy we had been up there,” she shares. In fact, Sohini suffered serious bouts of acute mountain sickness twice, and was once almost killed by it.

Kanchenjunga at sunrise

Kanchenjunga at sunrise

Giving an insight into her journey, Sohini says, “Our cars have rolled down slopes in reverse, once on the highway to Nako Lake and another time at Ravangla. A massive boulder — the size of four loaded trucks piled two by two — missed our car by seconds while on the way to Gurudongmar Lake in North Sikkim. To add to our troubles, in Kathmandu, my travel partner Sumita Rakshit was embraced by aggressive monkeys; in Patan, I was slapped by an old Nepali woman. Of course, there were the usual incidents of theft, bandhs, chauvinism and sexual harassment.”

While on her travel expeditions, Sohini reveals, she met several locals — some interesting, others inspiring. Narrating the story of one such gentleman, Sohini says, “We were trekking down from Chandrashila peak above Tunganath temple to Chopta, Uttarakhand. After a steep downward slope, we came to a tea stall by the winding route. The old tea-seller made us some black tea. While we sat sipping the hot brew gratefully, the old man chatted on about Mokkumath, his village below the mountain. In the middle of the conversation, he got up suddenly, went behind his shop and rang a large bell with all his might. The sound echoed all over the range. Then he came back to sit with us again.

Magnolias in Mussorie

Magnolias in Mussorie

“‘Why did you do that?’ we asked him. In a gentle, soft voice, he explained, ‘You see a lot of people climb up the mountain to have darshan at the Tunganath temple. But this is a difficult, steep climb, and many want to give up and go back. But if they hear my bell, they think it is the temple bell, and so they keep climbing. And once they reach me, I tell them that they just have a little more to go before they see the shivling.’ He was an illiterate villager of indeterminate age. But, thanks to him, hundreds of devotees succeed in climbing up to a temple at 12,000 ft, every day.”

The author also came across various tribes living in the mountains. With varied communities dwelling there, Sohini got to taste some exotic food too. “We have been open to tasting local food, which varied widely, not always to our advantage. We got to taste the ubiquitous black beans curry and rice at almost all lunch halts in Himachal; the thukpas and yak butter tea of Ladakh; a light curry made with fresh cream-green bamboo shoots (somewhat like cabbage, but tastier); and boneless chicken stuffed inside short bamboo poles and roasted at the fireside by an Apatani lady in Ziro, Arunachal Pradesh,” she shares, adding, “There were, however, some dishes that didn’t work for us. For example, a Sikkimese pickle made of fermented bamboo shoots and a fiery red chilli called dalle is quite an assault on the taste buds as well as the olfactory.” Adventure-freak Sohini wishes to go on the Kailash-Mansarovar yatra some day. Apart from travelling Sohini has varied interests too. About her hobbies, she quips, “I dabble in too many. Photography of course. And experimental cooking, which does get good reviews from long-suffering friends.”