Man who hates fame

Soma Das' book details life of Dilip Shanghvi, a self-made billionaire who briefly toppled Mukesh Ambani to become the richest Indian in 2015.

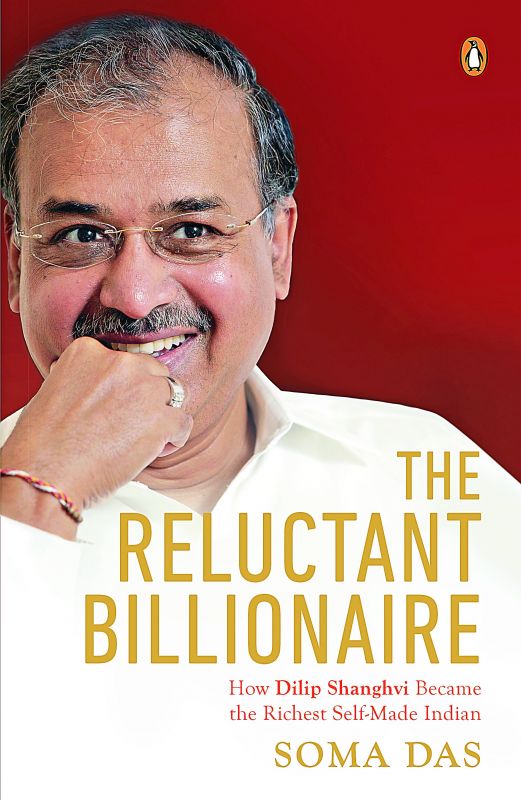

The title of the book — The Reluctant Billionaire: How Dilip Shanghvi Became the Richest Self-Made Indian — says it all. What the book has in store for readers is the untold story of Dilip Shanghvi, a self-made entrepreneur who toppled Mukesh Ambani briefly to become the richest Indian in 2015, but detests fame.

The reluctant billionaire by soma das, penguin random house Pp. 520, Rs 799

The reluctant billionaire by soma das, penguin random house Pp. 520, Rs 799

It was this ‘untold’ factor that fascinated author Soma Das, a business journalist for over a decade, to embark on a tough journey to trace the story of Shanghvi, the brain behind Sun Pharma, and write it down. “The inspiration for this book didn’t pop into my head one day. It sneaked in, nagged and haunted me till I yielded,” says Soma. “Business journalists, investors, pharma industry and the world of finance know the enigma that Dilip Shanghvi is. But a large section of the well-read India outside these circles has barely heard of him. Here is a man, untrained in degrees of sciences and management, who has created the largest medicine company of India, the fifth largest generic drug firm globally and one of the most valuable Indian enterprises, and also became the richest self-made Indian, all so quietly. How strange does it sound that so many Indians haven’t heard of him, who albeit briefly, crossed Mukesh Ambani to emerge as the richest Indian in 2015? How incredible does it sound, when you discover that

he had started out in a tiny shop in the bylanes of Kolkata? Other top league wealth creators, whether it be Mukesh Ambani, Gautam Adani, Sunil Mittal, Narayan Murthy or even the very private Azim Premji, are household names in India. Not Dilip Shanghvi,” she adds.

Soma cites Shanghvi’s unwillingness to share his story as one reason for this. Even people closest to him cannot claim to know him completely. “Once I asked a business associate-turned-family friend of his, ‘How close are you to Shanghvi?’ He thought for a moment and replied, ‘You have asked me a very complex question. There is no straight answer to this. I am close enough for him to discuss not only business, but his children’s career paths. I am part of all his important functions, but in my two decades of close association, I have never been invited to a dinner at his place’. Most people around him would echo this sentiment one way or the other that his mind feels like a black box.”

But, Soma, who found Shanghvi as the most interesting and least understood business mind of India, was as stubborn as a mule. “I wanted to know how he had done it all?” she says. The curious Soma searched for an answer all over, but couldn’t find any. That was the trigger. “I remember reading Steve Jobs by Walter Issacson, and wishing that I could read something like this about Shanghvi. The subject and the story started calling out to me again and again. In October 2014, I told Sun’s Head of Communications Frederic Castro that they should get a book written on Shanghvi. Three months later, I discovered a month-old mail in my spam from Penguin asking whether I wanted to discuss a book on Sun Pharma or Shanghvi. I was excited by the possibility and daunted by the impossibility of doing it. I knew Shanghvi, who serially turned down requests for media interviews, would obviously say a ‘No’. The process somehow acquired a different urgency after he became the richest Indian in March 2015. To my knowledge, at lea

st three other books had been commissioned on him around the same time. Ultimately, I ended up writing the book I was looking to read.”

Next hurdle was to get his consent, which they knew was unlikely to receive. Soma recalls, “We, the publisher and I, were not looking so much for his consent, as we were for his participation. The two shouldn’t be confused. In fact, right at the beginning when he said he was unwilling, we, as part of our protocol, informed Shanghvi that we would go ahead with our research with or without his participation. I had begun my research already as I continued to pursue for his participation. It was already a few months into the research when he agreed to give access to a list of people who have seen him up close. Access to these people proved crucial in understanding him. Without the insights of these co-passengers in his journey, the exercise couldn’t have even scratched the surface of his life.”

But, Shanghvi still felt the idea of writing a book on him was not feasible. “He was concerned that once we put his face on the cover, a lot more people would start recognising him and he would probably lose a bit more of his freedom. Our meeting was happening shortly after someone had walked upto him in the small South Indian food joint he frequented on Sundays and remarked, ‘You look so much like Dilip Shanghvi. If I hadn’t seen you in such a crappy place, I would have mistaken you for Shanghvi for sure’.”

Soma says he also tried convincing her that his life has been too eventless to merit a book. “In fact, almost towards the end of the research, in one of the sessions he told me, ‘You are working so hard. You should have chosen someone with more visibility — may be Sunil Mittal. That would have made a better business case for your book. After all, people want to read about people they know of’. It’s difficult to guess the exact reason behind his reluctance, but knowing him that was predictable behaviour.”

However, Soma is happy about her effort. She believes important stories like his would remain hidden if someone doesn’t make an effort. And, she feels grateful as she recalls 150 minds who opened up before a stranger to complete her writing journey. “Many of them broke down while relating emotional and painful memories,” Soma recollects.

According to her, the research process was about learning to handle a subjective material objectively. She prepared an original list, but names kept branching out of that list with people giving references of others. “My original plan was to complete the research first and then do the writing, but it so turned out that research work continued right till the very end of the first draft, and to a smaller extent after that as well. Only the proportion of research to writing changed from about 90:10 in the beginning of the project to 10:90 towards the end. That’s because every time I wrote a part, some unanticipated gaps in the narrative showed up, which then demanded more research. The manuscript took almost three years to complete,” says Soma, who does not preach any lessons via her book.

Like she says, readers can have their own interpretations of this work that heavily relies on memories, and draw conclusions. However, philosophies of Shanghvi that she finds interesting are his modest lifestyle that has less to do with morality and more with practicality and his Eklavya-Dronacharya model of learning. “He feels lifestyle shouldn’t become extravagant enough to start dictating professional decisions. So, he doesn’t show off his wealth, but he also doesn’t show off his austerity. Another interesting aspect is the way ‘he learnt in absentia’. When he analysed an interesting move by a leader or a rival, he ended up discovering more about the process he was studying than the source he was learning from. This way he ended up learning from leaders he never had any meaningful exchanges, like from the founder of Torrent UN Mehta, Dhirubhai Ambani and many more,” says Soma.

“For entrepreneurs, of course, one great learning from his journey is that ‘emotion is the engine, reason the driver’. In his core strategies, he always had absolute clarity about what he was doing and why. But, even when that strategy was not fully clear to people around him, their emotions were fully aligned to that goal because they saw it succeeding on ground,” concludes Soma.