Ode to the Ganga

Can a mere mortal do justice to the Ganga without being carried off by a flood of cliché? Six headstreams, five sacred confluences, life-giver to the northern plains of the subcontinent, soul waters of ancient belief, play course of adventure seekers. A celestial entity, the hard won fruits of steadfast human penance in myth, an ecosystem that has degenerated into the cloaca maxima of modern India — you see the problem? How do we begin to talk about this river of rivers, what do we not know already about ‘her’? (The Ganga is definitely a ‘her’ unlike her mighty cousin to the north-east, the Brahmaputra.)

Sunrise over the Ganga in Bihar

Sunrise over the Ganga in Bihar

Spread over 1.1 million square kilometres, the Ganga’s basin is home to a quarter of India’s population. It is an intricate web of tributaries and distributaries, of canals, waterways and run-offs. To capture its essence and its complexity is not a task for the faint hearted. Yet photographer Sondeep Shankar attempts to do just that in the book Ganga — A Journey that maps his own leisurely drift along the Ganga’s banks, a journey that in places echoes the delicious river idyll described by Rabindranath Tagore in his novel, The Wreck.

Boats on the banks of the Ganga at Chandannagar. The name Chandannagar is probably derived from the shape of the riverbank here, which is curved like a half-moon.

Boats on the banks of the Ganga at Chandannagar. The name Chandannagar is probably derived from the shape of the riverbank here, which is curved like a half-moon.

Cremations at Manikarnika Ghat

Cremations at Manikarnika Ghat

As you turn the pages of this book, you almost expect to encounter some little twenty-first-century Kamala, Tagore’s charming heroine, exclaiming eagerly over a fine head of carp or a basket of purple eggplants, orange pumpkins, cluster beans and other garden bounty. The Ganga river basin is described by the American architect Anthony Acciavatti, a Fulbright scholar who spent a decade plotting the region, as “the world’s most engineered river basin, a veritable ‘water machine’ and ‘a dynamic system, closely interconnected with the monsoon.’”

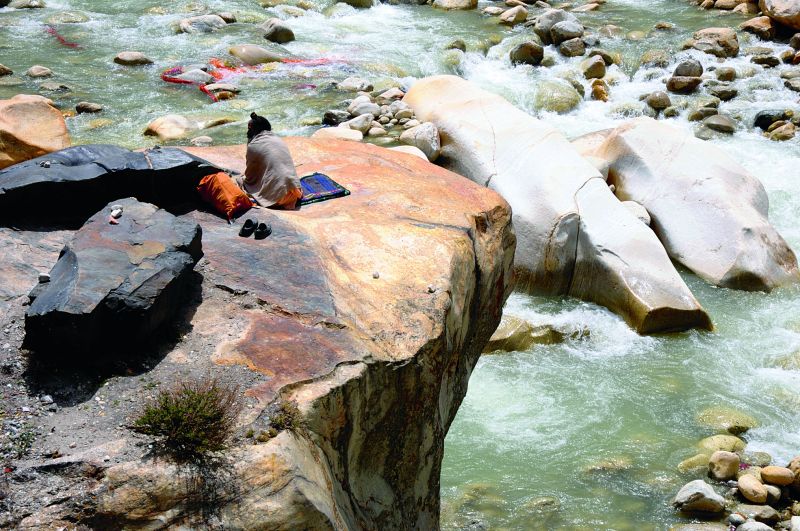

A sadhu sits in meditation on the banks of the Bhagirathi river at Gangotri

A sadhu sits in meditation on the banks of the Bhagirathi river at Gangotri

“This river,” he notably said, “can never be drawn as two parallel lines. It has layers of canals, well, roads, railway lines, human settlement, agriculture, and topography… ‘soft infrastructures’ like wetlands are well suited for run-off…temporary structures keep the river at a navigable depth in pre-monsoon months.” At its dirtiest, the holy river resembles a sewage pipe with the top-off. Nobody could possibly want to drink its waters now at places like Kanpur, where the tanneries pour an endless stream of filth into the river, or even at many a pilgrim site on its eroding banks.

Lighting oil lamps on the ghats of Varanasi

Lighting oil lamps on the ghats of Varanasi

A series of temporary pontoon bridges constructed over the Ganga for crowd management during the Maha Kumbha Mela in Allahabad in 2013

A series of temporary pontoon bridges constructed over the Ganga for crowd management during the Maha Kumbha Mela in Allahabad in 2013

It’s very odd today to think that Ganga water, reserved only for the royal family, was the biggest kitchen expense of the Mughals ever since Akbar’s time. There was a high-ranking officer in charge of just that, responsible for organising the supply of pots of water from the Ganga to Agra, Delhi and wherever else the Mughals went.

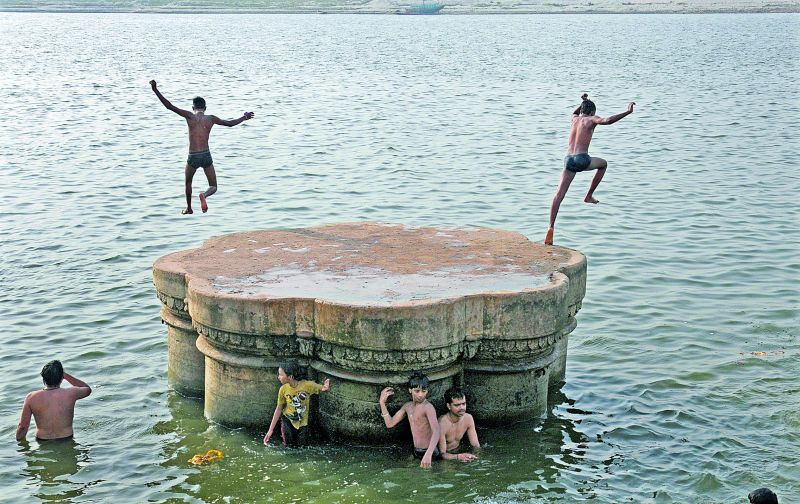

Leaping into cool waters at Varanasi

Leaping into cool waters at Varanasi

While Shah Jehan looked over his architect’s plans for the Taj Mahal on the banks of Yamuna, it seems fairly certain that it was Ganga water that he sipped from a jade goblet, sweetened perhaps by the juice of matchless langra mangoes from Varanasi.

Excerpt from: Ganga — A Journey by Sondeep Shankar; Introduction by Renuka Narayanan, Speaking Tiger, Rs 2,828, pp. 170