Mission impossible made possible

A powerful account of an Iranian woman's flight for freedom against wearing the Hijab under compulsion.

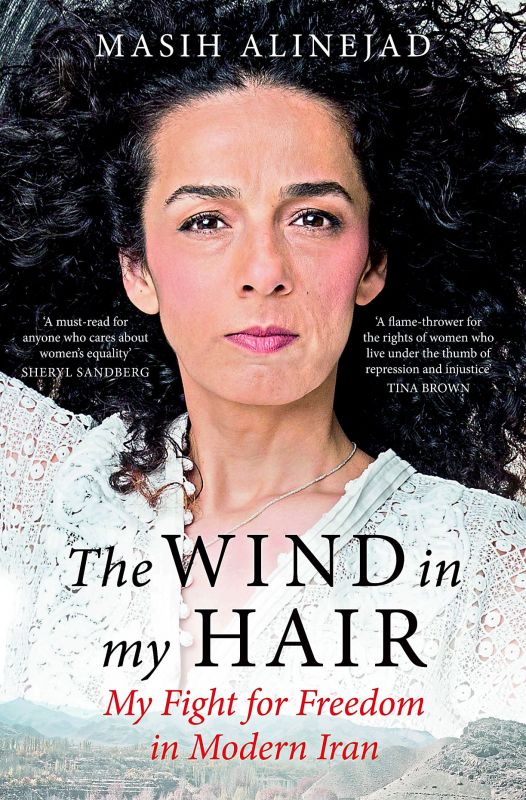

Masih Alinejad’s gripping memoir, The Wind in my Hair, My Fight for Freedom in Modern Iran, is an eye-opener to her persistent and brave fight against Iran’s repressive laws that mostly condemned women to second class citizens who have little freedom to follow their hearts. She has relentlessly fought against the mandatory compulsions imposed on women to wear the Hijab irrespective of their preference. Her real life saga has all the ingredients of a bestseller — from being arrested for political activism to a teen pregnancy, an early divorce that could have impacted anyone’s sanity. But Masih is a fighter, who overcame every obstacle that both life and the Iranian government has thrown at her. This internationally known journalist traces her roots to a little known village in Iran for this journey which begins on a compelling note. Here are excerpts from an exclusive interview with the US-based author.

You have not allowed your upheavals to influence the tone of your biography. It could have turned into a bitter narrative, but I find the approach balanced. Is that because you have made peace with your past?

I wanted my book to be more than a memoir. It is a journey, a geographical one from a small village in northern Iran to the capital Tehran and then to London and New York; it is a political journey of standing against injustice and learning to fight for my political beliefs and a personal journey of forging my identity by learning to say “no.” We often discover who we are when we say no. It is easy to say “yes,” and get along but much harder to stand for your beliefs and stand up for your rights. Also, I wanted to tell the story of the Islamic Republic from the perspective of a woman who lived through some of the most dramatic upheavals in the country.

From being arrested for political activism to a sudden pregnancy and a quick marriage and a subsequent divorce, your life has all the elements of a family drama? What kept you sane in the toughest of moments?

I am sure my enemies often think I am not sane! I didn’t start out with a plan but life often can derail the best plans. When you are going through an unplanned pregnancy and quick marriage, you don’t have time to think about the family drama but just surviving. I wanted to get married to leave the village and go to the city but never expected that I’d end up in a divorce. But, let me tell you something, surviving my divorce made me stronger.

“I’m the proud daughter of Ghomikola.” You have succeeded in putting Ghomikola on the world map thanks to your book. How does the tiny village react to all your achievements?

Funny you should ask. If you google “Ghomikola” the first result is me, Masih Alinejad.

Ghomikola is a tiny village and though folks have TVs, and all modern stuff, little has changed. Not everyone approves of my campaign but they are all aware of it. Let me tell you a funny story: my father had gone for a checkup at Babol, the nearest town and the doctor looks at my father’s id card and asks if we were related. Once he hears that his patient is my father, the doctor waives off his fees. Bear in mind that my father disapproves of my political campaign but he was caught in a bind. In fact, my mother tells me people from Tehran visit Ghomikola to take selfies!!

The wind in my hair, my fight for freedom in modern iran by Masih alinejad Rs 699, pp 394 Hachette India

The wind in my hair, my fight for freedom in modern iran by Masih alinejad Rs 699, pp 394 Hachette India

You have been in exile since 2009 and have indicated a strong yearning to go back home. But will your explosive memoir hinder that process?

I like nothing more than to go back to my country, be with my people and if the Iranian government allows free press, free expression, so I can campaign and work there, I’ll be back immediately. But it is not possible. My memoir isn’t going to make me any more popular with the Islamic Republic.

Prior to the Islamic revolution in 1979, Iran was a very evolved society. I have friends and relatives who talk about the nightlife in the 70s. Ayatollah Khomeini changed it all. I’m curious, have you interacted with women who have experienced that modern lifestyle and had it all taken away.

I have spent many hours with women from the generation before the revolution and it’s not just the lifestyle. Talking to these women, it’s as if Iran under the Shah was on a different planet. Women had the right to choose how they dressed, we had women with hijab and women without hijab. We had women entertainers and judges. Can you imagine a woman judge now? Impossible! But we had them 40 years ago. We had women ministers serving in the cabinet and as ambassadors. Truth be told, the Islamic Revolution was a revolution against women. It was a revolution to censor and subjugate women.

My Stealthy Campaign has gained over a million supporters worldwide, where women are defiantly uncovering their hair. I can understand when women are suppressed and wear the hijab out of coercion. But what I also see is that many educated and progressive women wear the hijab with pride as they are convinced that it protects them from evil. What would your response be to these ladies?

My fight is not with the hijab but compulsion. If women freely want to wear the hijab, that is perfectly fine with me. I am for women to have the right to choose; I’m against compulsory hijab. My own mother wears the hijab as does my sister. I have no problem with that. In fact, I’d love to walk side by side with my mother wearing her hijab in Paris or London or New York, and me without. I’d like Iran to be free enough so me and my mother can walk the streets of Tehran, she in a hijab, and me without.

I found the White Wednesday campaign very brave. Women taking to the streets without headscarves to fight for their liberation. But we are curious, what happens after they participate in the campaign, do they go back to wearing the hijab?

We have different campaigns depending on the level of tolerable risk. One of our other initiatives is #walkingunveiled and that is for women to go without a hijab every day. Some women cannot do that. That’s why, we focus on White Wednesdays because it is now becoming very well-known inside and outside the country. Our activists continue wearing white or go without hijab on other days too but we highlight it on Wednesdays.

Do you think it is adequate to ask women to throw their hijab, when it’s actually the men who need to be educated too? Because unless men learn to stand up for their women’s rights the subjugation will continue?

You are totally right. Our campaign needs the support of men if we are to succeed. We’ve had campaigns such as #meninhijab which received a lot of support. One of our videos was viewed 12 million times on one platform. Our campaign isn’t just political but also cultural. We need men to stop thinking of women as property, as sex objects and respect their rights. Just because some men are physically stronger, that doesn’t mean they should bully women. In fact, the younger generation of Iranian, doesn’t want to be seen as backward and bullying, and they support our cause.

How and why do you think the hijab became such a potent (if incorrect symbol) of woman’s honour?

I am not an Islamic scholar, and there are many arguments for or against hijab. I am not against hijab. I am against compulsory hijab — that’s a big difference. Look at Turkey, or Lebanon or Tunisia — the hijab is not mandatory. In the case of Iran, Ayt. Khomeini detested the Shah when he gave women the vote in the 1960’s. It has become a tool to censor Iranian women.

You became a journalist, and covered the Majlis (Iranian parliament), including Mohammad Khatamis’s re-election as president in 2001. Later, you strongly criticised Ahmadinejad’s presidency, publishing a series of damning articles in your column The Government of Denial for the National Trust newspaper. Where does this strong sense of fearlessness come from? Do you believe you like to court danger?

I am not brave, nor do I like to court danger. If anything, I’m a coward. But when I think an injustice has been done, then I have to stand up for what I believe. That’s when I don’t back down and I’ve got that from my mother. She is very quiet but once she feels wronged, she never backs down. When I was a reporter, I thought exposing corruption was my calling and I could not back down. Challenging Ahmadinejad’s chaotic government was next.

You got to understand one thing about me — I don’t care for money or property or any possessions. What motivates me is a great sense of justice. We all have a mission in life and I want to do all I can to fight the injustices that I can. I can’t fight them all but I have my little patch.

You had this strong desire to be the first Iranian journalist to interview Obama. Did that eventually happen? If not the interview, did you at least get to meet him?

I had two opportunities. I was invited to Cairo for Obama’s first address to the Muslim world. The trouble was that the Iranian authorities held my passport and would not release it so I could not go. When I reached the US, Ahmadinejad had been declared winner which made it complicated to see Obama. That’s what the State Department folks said. You have to understand that I was seen as very close to the Green movement, and with all the arrests and crackdowns, if Obama had granted me an interview, it’d have been seen as a signal.

I waited a month and gave interviews to a number of publications, like the New Yorker but no meeting with Obama. I declined an offer to meet with Hilary Clinton.

How challenging was it to write this book considering English has not been your strong point? Did you get feedback from your husband and son?

Ha ha ha… My husband and I wrote the book together. Obviously, I’m much stronger in my native tongue but I’m pretty good in English too. But it was challenging because I wanted to write in a Persian style of literature which is more lyrical but I couldn’t bring the same style in English.

What about translating the book, in your mother tongue, so that your countrymen can read it?

I’d be happy if the book is translated. Although, I have written articles about part of my life before in Persian. However. we need to find a translator and a publisher

Do you envisage a free Iran where women will be ultimately liberated from the shackles of wearing a hijab?

I dream of a secular Iran where religion is kept outside of politics and the state doesn’t try to control your private life. I expect to see an Iran where women have been liberated not just from compulsory hijab but from all discriminatory laws. That is my life mission.