Down to Earth

Founded on the pillars of design and ethics of sustainable living, permaculture is changing the way we live.;

Australian-Indian couple Rosie Harding and Peter Fernandes, who run a verdant homestead in what is emerging as Goa’s hippest village, Assagao, aspire to make ‘growing your own food’ the norm in homes across the country. The bucolic charm of their humble stead is similar to the quotidian, self-reliant goenkar home that traditionally grows its own food and poultry. Rosie and Peter’s garden of abundance produces a thicket of 250 different species and varieties of fruits, vegetables, perennial crops, calorie crops and herbs under the impartial Goan sun. This 700-square meter food forest, once a barren strip of land assessed unfit for vegetation, was transformed into a buoyant wonderland of lush greens by drawing primarily on the design principles and ethics of Permaculture.

Rosie plainly describes the ethos of permaculture as “the design and implementation of regenerative, self-sustaining and resilient natural systems that fulfill all of our human needs (food, shelter, health, social and cultural), whilst caring for the earth and all things that reside on it.” The term Permaculture is a contraction of two words — Permanent and Agriculture or Permanent and Culture, which is simply an alternative way of living or a lifestyle that is permanently mindful of its surroundings. Permaculture is also a way of creating systems and designs that emulate nature and is tightly spun around its 12 design principles, which can be applied to everyday living. The underpinnings of this design are firmly hinged on the non-negotiable rules: Earth Care, People Care and Fair Share.

Rosie and Peter got started a little over five years ago, when their search for locally grown organic produce, left them hard-pressed to find anything that would fit their needs. “We figured we might as well just get started and decided to grow our own food,” shares Rosie. These pursuits lead them to learn about permaculture, which was a much larger domain, covering many aspects of living apart from just food. Their learning had a great impact on the duo, gradually shifting their perspective from ‘how do we get good quality food’ to ‘how do we get quality food that is also good for our environment.’

Permaculture was first introduced to the world by an Australian biologist Bill Mollison and his co-developer David Holmgren in the 1970s. Its principles were primarily designed to mitigate the damage caused by modern agricultural methods that were draining both the land and its resources. As Bill tersely writes in one of his books, “Though the problems of the world are increasingly complex, the solutions remain embarrassingly simple.” Permaculture truly proposes embarrassingly intuitive solutions, in areas where man continues to be perversely counter-intuitive. Mollison died in 2016, but the roots of his movement have spread across 140 countries world over, and is on the upswing in India.

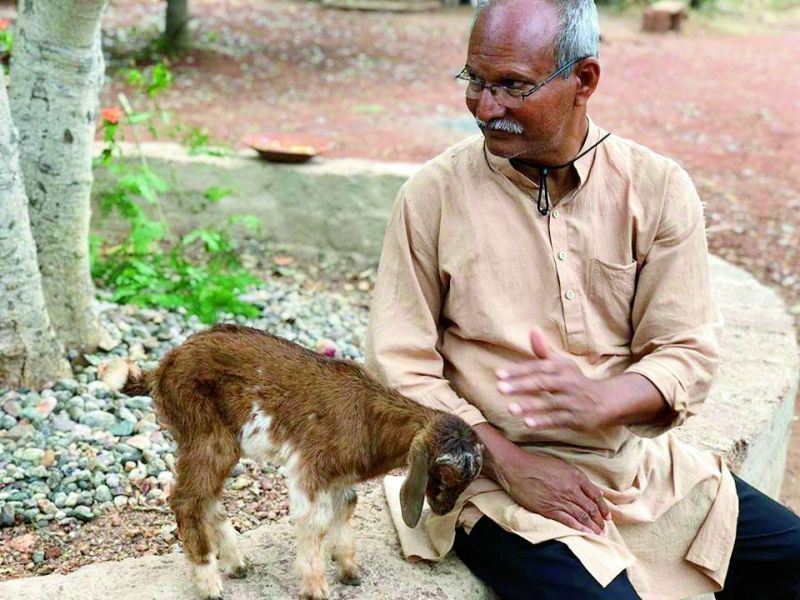

Among the first few permaculture pioneers in the country, Andhra Pradesh-based Narsanna Koppula took his first ever Permaculture Design Course under the tutelage of Bill Mollison and Robyn Francis in the 1980s, without ever realising it would be his life’s greatest lesson. At the time, Narsanna was mentored by Dr. Venkat, who invited Bill and Robyn to India to work with the farmers and further permaculture in the country. Narsanna believes the forest is the future and he spread his message through his non-profit organisation “Aranya Agricultural Alternatives” presently operating in the rural and tribal areas of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh.

He initially started working with small and marginal farmers in the 1980s, especially with women farmers from Andhra Pradesh with the sole aim to replace chemical-intensive farming with a more sustainable and natural approach. Above all, he wanted to break free from the exploitative relationship with nature that man has conveniently remained oblivious to, He says, “nature is not exploitative, it’s cooperative. I think that kind of ethical investment, ethical thinking is what we need to overcome the challenges of social, political, economic and environmental pollution that plagues us today.”

His wife Padmavathi Koppula has been instrumental in translating his Utopian vision of achieving ecological, ethical and sustainable farming methods in India through the pathways of permaculture. The couple’s body of work and achievements are as vast as the farmlands they work on. For the past 30 years, they have been actively working with the principles of permaculture, but it has taken its own time to come into the mainstream. Says Padmavathi, “Permaculture, what I believe, is to work with nature and not against it. On Planet Earth, every living being has the right to live. It has to be a win-win situation for all.”

While permaculture does not romanticise living at the roots, Padma believes, there is one-generation of knowledge gap and practice gap. “What we suggest is the younger generation connect with the older generation and practice traditional farming methods and you don’t have to throw away technology,” she quips.

A way of life

A lot of people might discount Permaculture as just gardening or farming or term it a neo-hippie trend with a cult following. But that is far from true. Permaculture is an applied science and it’s ability to describe the practical problems it seeks to solve has time and again dismissed these misgivings. The reason for this cites Rosie, “is because every permacultural system is anchored in the natural world and you can’t dissociate it from it.” While organic farming is one part of a whole, permaculture also entails social, economic and cultural aspects of living. “Outside of the farm, the future of permaculture is definitely in the socio-economic space,” explains Simrit, who runs the Roundstone Farms in Kodaikanal which is built around the principles of permaculture.

An example of applying permaculture in the socio-economic space would be to actively embrace diversity. As Simrit describes, “A healthy community would be one with a diversity of genders, races and beliefs that would almost definitely result in a more creative community. To ‘creatively use and respond to change’ – pertaining to permaculture principle No 12 — all communities should have the flexibility to respond effectively to change because change reaches us all,” she shares.

Simrit also actively conducts Permaculture Design Courses (PDCs) on her farm, which has become an exemplary model for others to witness the benefits of permaculture. She has been lucky to get local farmers to come and take part in her courses and assertively says, “The permaculture community in Kodaikanal has been growing.” Her next PDC will be conducted at her sprawling, pristine Roundstone farm in August this year.

Besides the trifecta — Earth Care, People Care and Fair Share, the sin non-qua of fundamentals include another important principle that most permaculturists endorse — to observe and interact with other beings, “People must understand that everything they do is connected to everything else,” says Narsanna leading us to another important tenet in Permaculture: One element must be able to perform many functions, “One problem-one solution is wrong in permaculture,” he stresses.

The basis of this principle is quite simple. It means if there’s a mutually beneficial relationship between two elements, it will automatically function very well. “I think the best testimony for interdependency is the absence of any ‘natural pesticide’ on a permaculture farm. We try to grow companion plants that confuse pests with their combined aroma and texture. Also, many permaculture farms have ponds and open water bodies, even though they don’t need the water. It’s to invite the dragonflies, frogs and snakes in to eat your pests. Chickens, ducks and geese are also often used to pick out slugs and other pests (a ‘win-win’ for all),” Simrit elucidates, adding, “We always grow multiple crops, just like you would see in nature. The biodiversity is great for the plants, and polyculture makes sure you always have multiple crops coming into harvest, so if one fails, you always have a backup.”

Narsanna corroborates, “The design should work by itself and it should demonstrate its own functions. Human intervention should be very limited; if you have to intervene every time, it means your design is wrong.”

When less is more

Meghna Kapoor, who runs the co-living and co-working space, Blue Lotus by Kyo Spaces in Goa is a permaculture practitioner who believes that one doesn’t need to live off the grid or own a farm to practice the virtues of permaculture. All one needs to do is make more eco-conscious choices. “Permaculture can be easily adopted in any lifestyle. We can bring around a sea change by simply cutting our consumption pattern,” she says. “I started making small changes by carrying my own bag and ditching plastic, buying products that are sourced locally or even second-hand clothes. At Blue Lotus, we also grow some food because there’s a place in our garden,” she shares. Meghna also segregates and composts her waste regularly. “We’ve got two compost pits in the garden, so instead of just burning old leaves we compost them,” she adds.

The banana circle in permaculture is a great way to put organic waste and excess water to good use. All you need to do is dig up a ditch, take the soil you’ve scooped out and mound it around the pit. This is where you will plant your bananas and other symbiotic fruits that will mutually benefit both the plants. The pit serves as a compost pile and voila! You are automatically generating less waste, growing your food and serving the environment. (One element- many functions)

One major hitch for urbanites aspiring to grow their own food is the space crunch. “Irrespective of the space or land type, at the end of the day, you must work with what you have access to,” says Rosie remembering her first experience of working on a rooftop terrace in an apartment building in a more urban area. “Now that’s what we had so that’s what we started with,” she says.

Permaculture is a tree-based system and in urban areas, one might not be able to do much on community rooftops or rental homes. But Edible Routes, an organisation in Delhi helps people walk the talk by building kitchen gardens in urban homes, no matter how small a space. “Like a very simple example would be mulching. It is basically leaving leaf litter and covering the soil as much as possible to make more favourable conditions for plant growth. This is something that’s part of permaculture that we’re able to apply in what we do in urban areas,” says Fazal Rashid, who handles farms and urban garden operations at Edible Routes.

Last monsoon, Edible Routes planted around 1,000 trees at various clients’ places. These plantations were designed in a way that they don’t obstruct the agriculture, the kitchen garden or the crops simultaneously being grown on the land. The trees were also chosen in a way where they are very energy efficient, local and native varieties that don’t require too much human intervention or maintenance. “As urbanites living in Delhi, the real work we’ve done in permaculture in the past three to four years is the community we’ve built of urban people whom we’re putting on a path that follows permaculture principles — especially Fair Share, because we don’t have land in Delhi and don’t have the possibility of growing trees or crops anywhere,” avers Fazal.

This four-year-old team of 22 members shares the same vision of sustainability. They have been training people in kitchen gardening, connecting people to a community of gardeners and are building a community that understands more the functions of nature and how fair share, people care and generosity are a part of the ethics of permaculture work. Says Fazal, “I think those are the real seeds of permaculture that we’ve sown, what we are reaping, in turn, is the kind of human crop (community) we’ve grown.