Theyyam, Indian shamanic shuffle that can unravel anthropological mysteries

It can be safely said that Theyyam is an ancient artform;

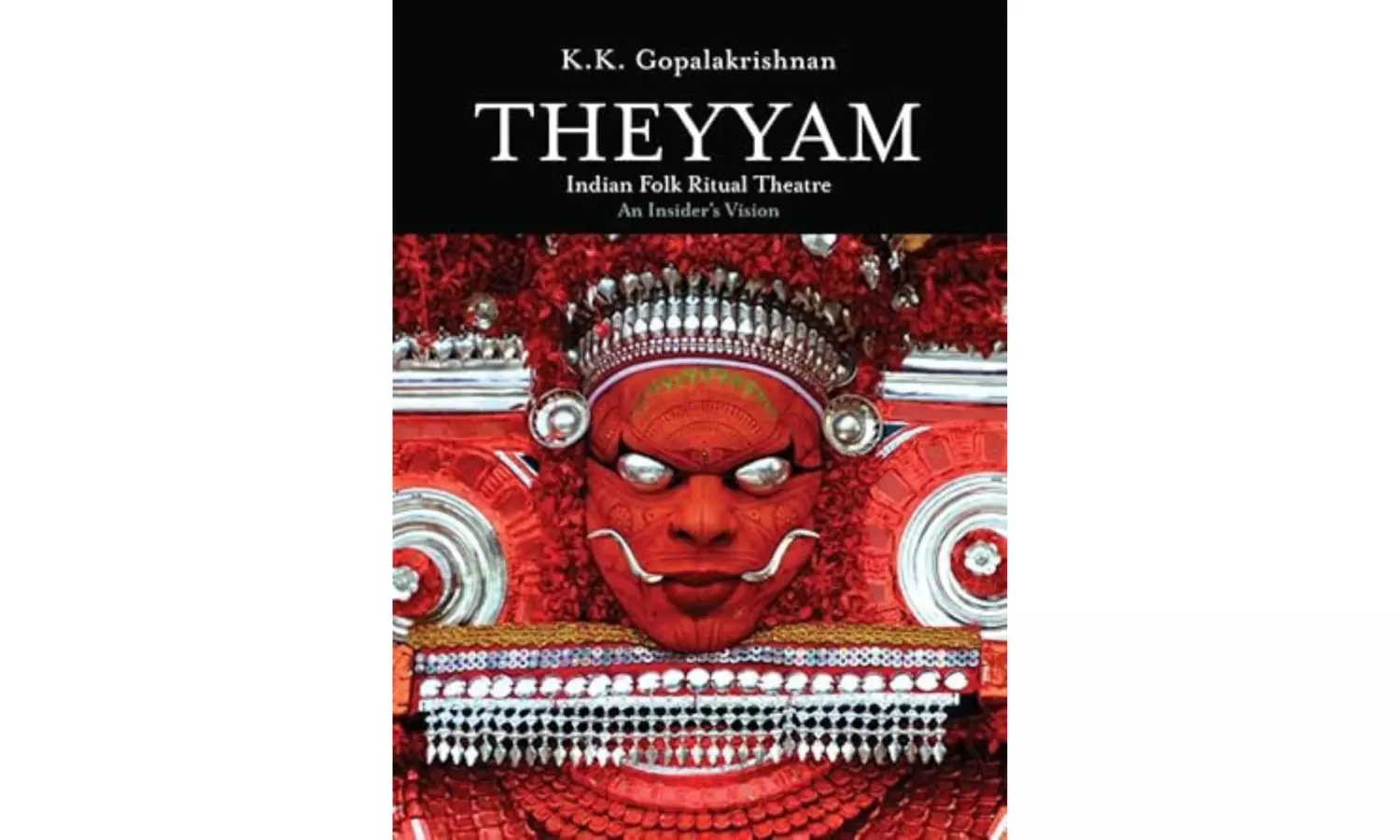

Mime. Theatre. Worship. Trance. Dance. Art. Music. Story. Now imagine a spectacle comprising all these further augmented by esoteric chanting and extravagantly colourful makeup and attire. In which the performer takes on the attributes of the powerful deity, indeed, for the duration of the performance, becoming god. And in this role, he is the oracle, spelling out curses and blessings and eye-opening diagnoses on the richest of village elders, not sparing even the head of the house that is hosting his show.

Variously known as Bhuta (Karnataka), Kolam (Kasaragod) and Thira (Kozhikode) and owing its footwork to Kalariyapattu, the indigenous martial art legacy of the land, Theyyam is believed by scholars to be the stockroom of the anthropological history of Kerala. The author himself describes it to be “the divine force of Dravidian culture that existed in the region much before the impact of the Aryan influence” in his treatise. The Aryans came to Kerala from Maharashtra. The first Sanskrit inscription found in Kerala was at the Adoor temple in Kasaragod. It is in Kannada script and is believed to be dated around 700 CE. It can be safely said that Theyyam is an ancient artform. It flourished during the reign of Kannur's Kolathiri dynasty which later came to be known as the Chirakkal dynasty. Aside from Kutiyattam, the classical dance, Kathakali, is said to have been influenced most by the tradition of Theyyam.

Theyyams are held at homes and centrally appointed open spaces called kavs. The artiste is known as kolakkaran; however, if he is outstanding, he will be bestowed with the title of Kalaippati and will henceforth need to be addressed as acharu. Then, during off-season, he can no longer take up manual labour to sustain himself. Performers are male. They usually hail from 14 dalit communities of whom the Vannan and the Malayan are the most prominent and predominant. The Thiyyan community plays significant role as patrons.

Every Theyyam is preceded by the performance of a thottam and a vellattam. A thottam comprises an impromptu thought poetically rendered accompanied by some religious verses or shloka. It is followed by the ritual of velattam wearing the beginning of makeup and a minimum of costume. The Theyyam season usually starts in the last week of October, ending in May. Very interestingly, the object of worship in Theyyams is not limited to the traditional Hindu gods but may include local deities; animals such as monkey, boar, tiger, crocodile and snake; one's ancestors; warriors and martyrs; and forest gods. Herein lie alternate histories and legends that are yet to be explored made more attractive by the fact that there are over 250 Theyyams in Kerala alone.

Take the story of Bageshwari or the Muchilottu Bhagavati, a scholar and orator born to an ordinary family who participated in a region-level discourse with a vow to marry whosoever defeated her but was subsequently given a bad name out of spite after she won the debate, which drove her to suicide. Her opponents nastily imputed promiscuity to her as the source of her quite sex-secular wisdom. Then there is the Kallurutty from whom pregnant women are advised to stay away.

The artistes are often seen to perform feats of endurance and extreme courage such as dancing with coconut fronds or burning wicks tied to the waist, wearing a 12-metre high crown, walking on embers, or wearing silks and then running through fire.

Hindu-Muslim syncretism is another unique aspect of Theyyams. The Muslim or Mappla Theyyams either venerate someone virtuous or commemorate someone wicked who supposedly got killed by God's will. Mappla Theyyams sometimes involve climbing nearby palms and plucking coconuts, often resulting in accidents. Incidentally, the Arakkal royal family which patronised these Theyyams is the sole Muslim dynasty that followed the matrilineal system, perhaps even in India.

Beautifully illustrated, this is a book of rich and extraordinary detail, prepared painstakingly by K.K. Gopalakrishnan. It can set off many a scholar and social reformer on a quest, but on the other hand, is an appeal to conserve this rare heritage which now rest on the shoulders of poverty-stricken artiste families struggling to scrounge out a living amid uncertain patronage, state or individual.

Theyyam: Indian Folk Ritual Theatre, an Insider’s Vision

By K.K. Gopalakrishnan

Published by Niyogi

pp. 352; Rs 6,000