Unpaid at home, underpaid at work

The share of Indian women in wage employment , at less than 20 per cent, is lower than that in Sub-Saharan Africa.;

On the face of it, women are being welcomed into every profession, including in combat roles in the military. But barriers at home and biases at work continue to ensure that women’s contribution to the economy remains unmeasured, unrecognised. That may be why, in a time of high growth, the number of women in the workforce is falling, not rising.

Development is like a cart with two wheels — one man and one woman. If one of the wheels isn’t moving, the cart won’t go very far,” said former World Bank president Paul Wolfowitz at a conference in Washington, quoting a Pakistani woman.

And who would know this better than us South Asians? Yet, this region remains one of the most discriminatory in the world, with the gender gap in labour force participation second only to that in Northern Africa, where women are prohibited from working for religious reasons.

The reasons are not far to seek. A lesson in the Class X social science textbook in Chhattisgarh in 2015 claimed that “working women are one of the causes of unemployment” in the country. This regressive mindset is quite prevalent in the country, where women are discouraged from working full-time by their families or they relinquish their career prospects ‘voluntarily’ to manage household chores.

According to International Labour Organisation (ILO), less than 20 per cent of women in India have wage or salaried jobs, while over 50 per cent are involved in part-time self-employment. Thirty per cent of Indian women, however, are doing what ILO calls Contributory Family Work, or exclusively unpaid household work.

Compared to this, the proportion of women in wage and salaried work is 89.4 per cent in North America, 88.4 per cent in Europe, 75 per cent in Arab states, 66.6 per cent in Latin America and the Caribbean, 63.2 per cent in Central and Western Asia and 55.3 per cent in Eastern Asia. The share of women in wage employment is particularly low in sub-Saharan Africa at 21.4 per cent and in Southern Asia at 20 per cent. In India, it’s even lower than that!

The lower participation of women in formal employment makes Indian women the lowest direct contributors to the country’s economic activity. According to a McKinsey study, India has a lower share of women’s contribution to GDP at 17 per cent than the global average of 37 per cent. In contrast, China’s women contribute 41 per cent, those in Sub-Saharan Africa 39 per cent and women in Latin America 33 per cent. But is that a true measure of women’s contribution to the Indian economy? What’s not measured goes unrecognised.

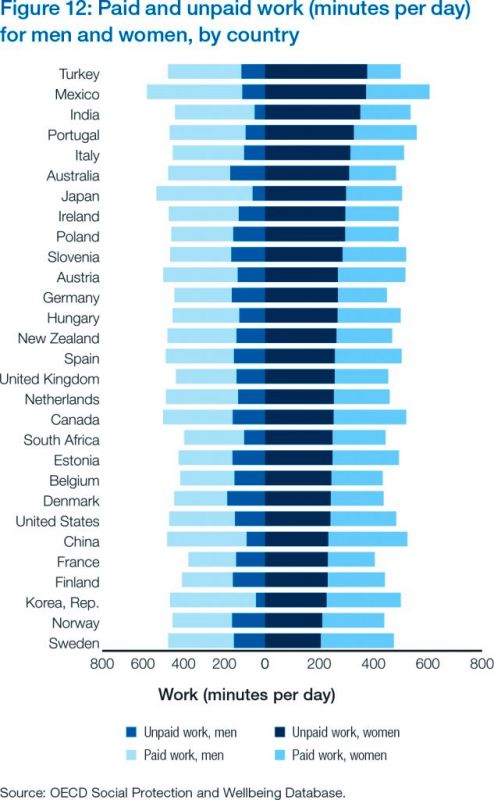

The ILO report says that both in high and lower income countries, women work fewer hours in paid employment, while performing the vast majority of unpaid household and care work. “On average, women carry out at least two and a half times more unpaid household and care work than men in countries where the relevant data are available,” it said.

As Jayati Ghosh wrote in The Guardian, “the invisibility of such women workers is appalling, because such work is essential to the survival of society and provides a huge and unnoticed subsidy to the formal economy.”

But where women’s contribution to the economy is formally measured, there’s more bad news for India. According to National Sample Survey Office’s (NSSO) surveys, the employment of women is lower in urban areas at 21 per cent compared to 36 per cent in rural areas, which is low given the state of economic development that India is in. Digging into historical data shows an even more negative trend: the number of working women rose from 2000 to 2005 from 34 per cent to 37 per cent but thereafter has been falling steadily, touching 27 per cent in 2014.

This decline, the World Bank’s World Development Indicators report noted, happened during a period of unprecedented economic growth, shattering the conventional wisdom that economic development leads to gender parity and higher number of women in the workforce.

Two factors could have caused this decline. “A majority of people in India still do not consider woman’s income as the mainstay of the family. Therefore, as the male member’s income increases due to the higher economic growth, there is tendency for women to go easy on taking up a formal job. Another factor is girls’ education. As NSSO surveys take into account employment of people aged above 15 years, higher disposable income in the family - during higher economic growth period — could have allowed girls to pursue higher education, which they would have been denied otherwise.”

Klasen S. and Janneke Pieters, who studied the stagnation of women in the labour force in urban India at University of Gottingen in Germany, have found other reasons. Studying female labour force participation over the past 20 years, they found a U-shaped pattern of association between female education and labour force participation. This means women whose level of education is low typically tend to be more inclined to work. The propensity to work was found to be lower among women with medium levels of education, while women with higher education were keen on taking up jobs. The factors that led to such a U-shaped pattern between a woman’s education and her propensity to work was discussed in the ILO. Its report surmised that the reason behind “the decline of women’s participation in the workforce in India could be the result of the fact that there are just a handful of sectors that employ (educated) women. Also, there are only certain jobs that women get societal approval to do.” “Women in India tend to be grouped in certain industries and occupations, such as basic agriculture, sales and elementary services, and handicraft manufacturing,” the report states.

Demand-side effects also play a role in the decline in women’s participation. Jobs which women with moderate education prefer to take up, such as clerical and office assistants, have grown slowly.

Another reason for their disinclination could be job conditions and gender equality issues. The Human Development Index (HDI) report says, for instance, that India fares worse in gender parity even compared to countries like Bangladesh, Ghana, Malawi, Kenya, and Uganda. Indeed, there are 26 countries with lower per capita income and Human Development Index (HDI) than India that nonetheless show higher levels of gender parity, suggesting that apart from economic development, non-economic factors like social attitudes influence gender equality in a society.

In a McKinsey survey, the reasons for this state of affairs became clear when more than half of the respondents in India agreed with the proposition that “when jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women” and that “when a mother works for pay, the children suffer.” It’s this kind of attitude, and its effects, that led another McKinsey report to note that, “Indian women face high or extremely high inequality on all five indicators related to work: labour-force participation rate, professional and technical jobs, unpaid care work, wage gap and leadership positions.”

It’s unsurprising then that while NSSO data says that only seven per cent of women, who have cleared Class 12, are working as senior officials, compared with 14 per cent of men, and only 38 per cent of working women have professional, technical jobs, a global survey conducted by Grant Thornton found that India has the third lowest number of women in leadership roles. And NSSO wage data shows that women, on average, are paid 30 per cent less than men in the country for the same kind of job, irrespective of the professional level.

Pay parity and lack of presence in leadership roles are issues worldwide, not just in India. The World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs report goes beyond looking at societal attitudes to working women and cites issues in the corporate setting -- lack of work-life balance, unconscious bias among managers, lack of female role models, lack of qualified incoming talent, women’s confidence and aspirations - as key reasons that hinder women in pay and promotion matters. But State Bank of India chairperson Arundhati Bhattacharya, one of a handful of exceptions to the rule, gives a more grounded view — that few women get to the top because for most, it’s almost determined at entry that they would quit midway through their careers to take up responsibilities at home. “In India, women are still considered the primary caregivers. It is expected that they sacrifice their careers to look after the family if required.”

If, on the other hand, women could participate in the economy on an equal footing with men, a McKinsey report said, India could add $2.9 trillion to its GDP in 2025, or close to 60 per cent of the $5 trillion economy India is projected to be by then. Even if India just managed to match the best country in the region on this measure, it would add $700 billion to its economy and increase its growth rate by 1.4 per cent. Typically, a 10 per cent increase in female labour force participation leads to an increase in GDP growth of 0.3 per cent. For India’s growth, therefore, the glass ceiling is the limit.