Mythological stories are not about Gods, they are about human nature, says V Ramesh

Vizag-based artist speak about his style, inspirations, struggles and the stories that his canvases tell in a Raza Foundation event.;

New Delhi: Indian mythology and ancient puranas are not made-up stories about Gods; they contain the universal truths about human nature and are timeless in their appeal, according to artist V Ramesh whose works have captured the attention of art aficionados for their distinctive narrative vocabulary rooted in India’s sacred and literary culture.

In a free-flowing conversation with author and journalist Madhu Jain on Tuesday at the Art Matters dialogue series organized by the Raza Foundation, the Vizag-based artist spoke about his style, inspirations, struggles and the stories that his canvases tell.

Ramesh is among the rare artists who have successfully married abstraction and realism in their works, and he has distinguished himself in this group by integrating “voices from poetry and imagery culled from mythology”.

Madhu Jain referred to the allegory, metaphors and stories as elements that appeared to give his works a time continuum.

“I don’t think time is a linear factor or that something should be more relevant to us now because we are living in the 21st century,” said Ramesh. “Every idea is relevant to us because they affect us. Mythological stories are not about Gods, they are about human nature and the human psyche.”

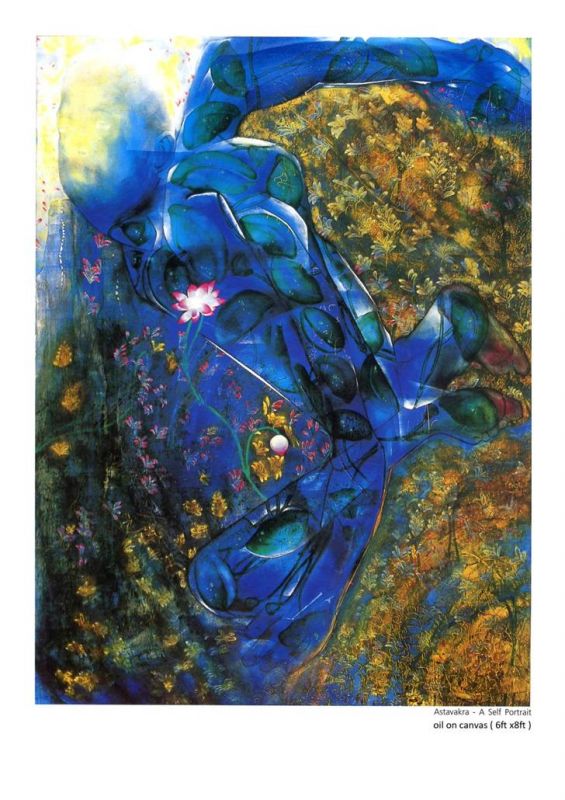

Astavakra- A Self PortraitHe referenced a painting of his called “The Thousand and One Desires” in which he depicted the legend of the God Indra after he is cursed to be covered with a thousand eyes for his lustfulness and greed.

“Greed has been around there since time immemorial. We may be advanced technologically and socially, and yet humans still covet things that do not belong to them, that has not vanished; that is what the stories tell you. And it’s in all cultures, not just Indian. I don’t think the storytellers of old were trying to be moralistic, they were just telling you how things were; it is up to you to take what you want from it.”

This timelessness, he said, was what he tried to explore in his own paintings; such as the one of Ashtavakra, whose story depicts the primacy of wisdom over physical beauty; or that of Karaikal Amma, a 5th Century Tamil poet who seeks a boon to be made so ugly that no man should ever desire her, and that she be freed from the bonds of physicality to roam the earth naked and write and recite her poetry.

Ramesh’s liberal use of verses from medieval women poets was another distinct feature of his works that Jain noted during the conversation. Besides Karaikal Amma, he has also referenced the poetry of Akka Mahadevi, a 12th century Kannada poet; Lal Ded, the 14th century Kashmiri Mystic; and Andal, the great Tamil saint.

His extraordinary discovery, he said, upon reading the works of these women separated by both time and geography was that they were essentially saying the same things, the words had the same resonance although the metaphors they used were distinct to their own cultures.

A Thousand and One desiresTheir stories, experiences and works were fascinating, he said, especially that of Andal, “because it has so much of erotic overtones which people suppress”.

“Andal’s father was supposedly a garland maker for the temple deity and as a young girl, she would secretly wear these garlands before they were sent to the temple, which was sacrilegious. One day her father discovers the misdeed after finding a strand of her hair in the garland. He makes a new one and puts it around the deity. In the night he gets a dream where Lord Vishnu tells him he misses the garland worn by the daughter because he misses the scent of her body.”

“This is beautiful,” added Ramesh. “When people talk about devotion or bhakti it has overtones of eroticism and physicality which most people deny. That intimacy with the deity and the truth is evident even in the hymns of Akka Mahadevi. We seem to have lost that in our skeptical outlook to the world around us.”

He decried the Indians’ general loss of “sensitivity” to surroundings. “We have lost our sensuality, our capacity to be sensitive to the physical attributes of life around us, like a scent or touch. How many children these days would react to the smell of the first rain falling on dry earth? Many don’t even come out of their houses when it rains.”

“Sometimes it is astounding,” he said,” to see that outer garb may change, but in essence, the way things are the way people are remains the same for centuries. Poetry and painting from ages ago can still be relevant; they have the ability to arouse emotions and move you, if you are open to it. I think we all should be a bit more sensitive to these voices which come from everywhere and let them in.”

The discussion also dwelt on Ramesh’s evolution as an artist capable of “speaking the languages of both abstract and realism without guilt”, his deep spiritual experience from a chance visit to the Ramana Ashram and his difficulties in working without an artistic precedent for including devotion, bhakti or ibadat in paintings in the manner that he has done.

Ramesh, who has also been teaching at the Department of Fine Arts, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam, since 1985, spoke hopefully about the artistic spark and the spirit of inquiry among his students.

The dialogue last evening was the 49th in the Art Matters programme hosted by the India International Centre in Lodhi Estate. A running series for the past five years, it has witnessed conversations with eminent personalities and expert practitioners drawn from the world of ideas, literature, visual arts, performing arts, among other disciplines and traditions.

A Poet in her own wordsThe 50th edition on November 15, 2017, will feature renowned classical dancer Dr Sonal Mansingh in conversation with writer and critic Manjari Sinha.