A new compact needed between media & State

It was brave of the pundits whom the anchors had assembled to keep up the pretence of being in the loop.;

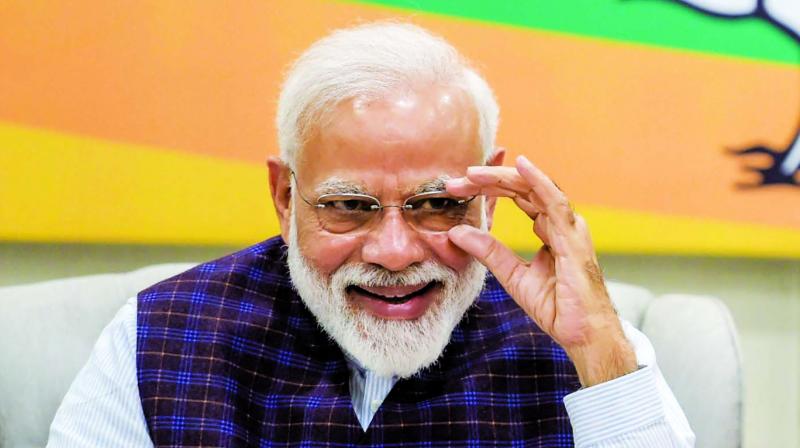

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, now at the zenith of his power, must appreciate the role that the media played in building him up as a virtual demigod. The nature of this media is a discussion for another occasion. The Modi establishment has in its power to confer on this media something it has not had for a long time — credibility. There are outstanding exceptions like Ravish Kumar of NDTV. But most of the electronic media has placed its credibility at the service of the ruling party. That is why the media looked a little embarrassed on the day the government was formed. It became so clear that the Modi government keeps it at arms length. None of the anchors had any knowledge of either the ministers or their portfolios. This is unusual for a lively democracy.

Of course, it is the government’s prerogative to keep secrets. Fair enough. Secrecy is a high value on, say, the nuclear issue. But a few leaks on portfolios would have added to the credibility of an otherwise committed media. With so much power in his hands, the Prime Minister can afford to have his team be on talking terms with the media. A government cannot be expected to take hundreds of journalists into confidence. But surely a handful can be trusted. Information then has a way of percolating down.

The great TV anchors, God’s gift to Indian journalism, who have been Mr Modi’s shrill town criers, looked sheepish covering the spectacular swearing-in ceremony at the forecourt of Rashtrapati Bhavan. These media stars from the loyalist school of journalism kept state secrets so deep in their hearts that they revealed not one portfolio, not even at the time when the portfolios would be announced. There is an Arab saying: “He who knows not and knows not that he knows not is a fool to be avoided.”

It was brave of the pundits whom the anchors had assembled to keep up the pretence of being in the loop. Some of the pundits, who looked particularly distraught for having made no contribution to the discussions, leapt with excitement when a lady in a dark sari strode towards the lectern. “Sadhvi Niranjan Jyoti”, one exclaimed. “The sadhvi of the haramzada fame”, added his neighbour helpfully. In the midst of solemnity, this struck a discordant note. The anchor could have explained that the sadhvi, while trying to rhyme Ramzada with haramzada, had quite inadvertently ended up describing Muslims as “bastards”.

The manner in which the Cabinet cards were held close to the chest reveals the government’s singular lack of rapport with the media. The lack of transparency in government formation would have been understandable if the Prime Minister had to juggle and balance multiple coalition partners. In this instance, he is the master of all he surveys.

By sitting tight on an innocuous Cabinet list, what signal is Mr Modi sending to his Cabinet, party, media and indeed the country? That he runs a tight ship? But we know that.

In the ultimate analysis, the message is loud and clear: Information is power and this power, like all the others, is held by Mr Modi and Mr Modi alone. Those who have started saying that Amit Shah knows more are troublemakers. Remember his pitch during the campaign: Wherever you press the flower button, “the vote will come to Modi” (pointing his finger at himself).

The multiplicity of the media and its rapid expansion to accommodate the post-liberalisation advertising, altered the State-media equation. This happened in the 1990s. But relations between the media and the State were vitiated much earlier, by Indira Gandhi’s Emergency. These relations have to this day not been truly composed. A section of the media compromised with the regime, imagining the Emergency would last. But a much larger section fought Indira Gandhi tooth and nail. Journalists in the latter category altered the basic terms of endearment. In a classical framework, the independent media was expected to have an “adversarial” attitude towards the government. But the fierce antipathy generated during the Emergency caused a simple replacement of the term “adversarial” by “oppositional”.

The feisty publisher of the Indian Express, Ramnath Goenka (RNG), who had staked his newspaper empire fighting Indira Gandhi, sought to make peace with her when she returned to power in 1980. Alarmed at this turn, Romesh Thapar and other champions of civil liberties pleaded with RNG. “You and Arun Shourie have been a two-man opposition to Mrs Gandhi.” They implored him to keep up the struggle. RNG’s response was pithy: “A newspaper cannot function like an Opposition party.”

Indian journalism, accustomed to the Congress culture since 1947, has had to cope with something radically different since 2014. Atal Behari Vajpayee was an interregnum of an unexpected order. He was the best Prime Minister the Congress never had.

The fawning media is, of course, a function of crony capitalism. The media is a secondary investment by business houses which they place at the disposal of the State in order to buy favours for their principal businesses. The alternative media, manned by independent journalists have their durability subject to fluctuations. All concerned must have a conversation. Are the channels and the information and broadcasting minister open to a dialogue? Without a new media, there is no democracy.

To be on talking terms, the sides have to fall back on the classical dictum. “In a democracy, people elect a government of any hue. The role of the independent media is to support the people’s choice on an issue by issue basis.” The stance is not oppositional but adversarial. For example, the media would reserve the right to tear into the administration whenever vigilantes lynch alleged beef sellers or young couple who cross lines of caste and community. And, applaud where applause is due. Without this kind of a compact, we shall have propaganda, not journalism.