India was Zimmer's muse, bedrock of his friendship with Jung

Jung's engagement with India culminated in a visit in 1938 where he saw the temples devoted to Kali.

A new book, A Mediated Magic, looks at the Indian presence in Modernism between the years 1880 and 1930. Among the various essays in the volume, on theosophy and musical culture, on Anna Pavlova and Indian dance, and on Tagore and Ananda Coomaraswamy’s vision for Indian craft, there is also an essay on Carl Jung’s relationship with India and his fascination with the Indian sacred texts.

Jung’s engagement with India culminated in a visit in 1938 where he saw the temples devoted to Kali.

The essay deals in part with Jung’s relationship with another noted Indologist Heinrich Zimmer and goes on to state that Zimmer was so profoundly influenced by Jung’s interpretation of the Sanskrit texts that he felt it had “unlocked the master key to comparative symbolism”.

Jung had made a study of Buddhist, Hindu and Taoist practices in personality development and in his seminal work Liber Novus, he had quoted from the Bhagavadgita on the nature of dharma, “whenever there is a decline of the law and increase in inequity, then I put forth myself for the rescue of the pious and for the destruction of the evildoers. For the establishment of law, I am born in every age”. This, of course, refers to Krishna as an avatar of Vishnu but Zimmer had read Jung’s The Secret of the Golden Flower and this had a profound impact on him.

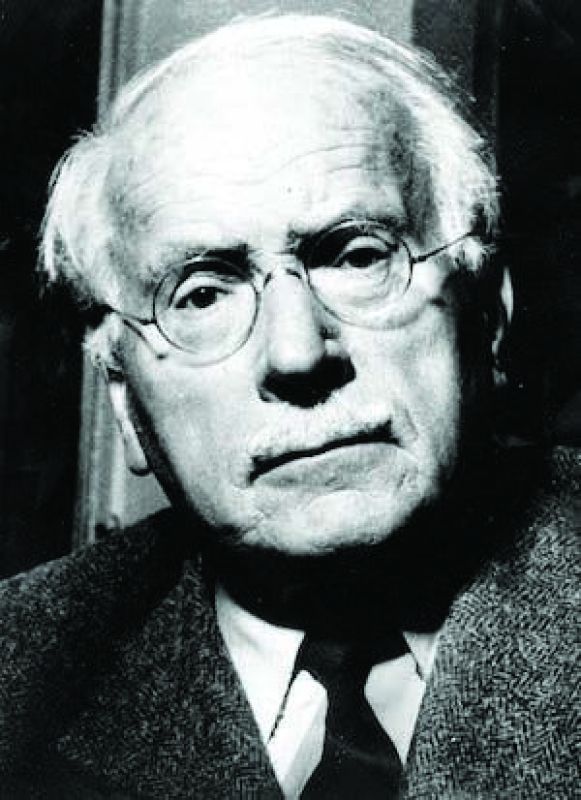

Carl Jung

Carl Jung

At their meeting in 1932, Zimmer told Jung, “What struck me then was the sudden insight that my Sanskrit texts were not merely a collection of grammatical and syntactical problems, but they also contained a substantial body of meaning.” In Jung, Zimmer found someone with whom he could have a close, intellectual and spiritual relationship. Zimmer was willing to have Jung take on the role of a guru, a Zen master much like the role of a Hindu sage. Jung, on his part, was quite willing to assume this role. He too knew of Zimmer before they had met. He had read Artistic Form and Yoga in the Sacred Images of India. It was later reprinted and published in India, inspiring students of Indian religion and culture. Jung was to write later of that first meeting, “I found him to be a man of lively temperament, a man of genius. He talked a great deal and spoke very rapidly, but he could also be an excellent, attentive listener.”

Zimmer’s listening skills were to be put to test when, at a lecture at the Analytical Psychology Club of New York in 1942, Zimmer mentioned that the first teaching he received from Jung was neither oral nor written. “I was taught by the pictorial script of a mere gesture after the famous manner of the masters of Zen Buddhism, who prefer to teach without words by mere gestures and attitudes. In this case, it was a gesture of both his hands, and in one of them, he held a bottle of gin.” Zimmer and Jung were standing together at the lunch buffet after the former’s lecture on Hindu yoga psychology.

Zimmer was excited as Jung had possibly praised his lecture and was also privileged that Jung was pouring gin from the bottle into a glass of lemon squash held by Zimmer. Zimmer, very excited at this privilege, and knowing that Jung perhaps knew more about the human psyche than anyone else, naively asked Jung about his opinion of the Hindu idea of the transcendental self.

“But he, without so much as disclosing his lips, poured gin from the bottle in his right hand, and with forefinger of his left hand, persistently pointed to the rising level of the liquid in the glass, until I hastily said ‘stop, stop, thank you’.” It was a gentle and indirect way of making Zimmer come down to earth from the lofty heights of his question, and to abandon the soaring and speculative flight to transcendental spheres!

Zimmer wrote prodigiously on India. Apart from Artistic Form and Yoga, some of his other works in English included Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilisation, Philosophies of India, The Art of Indian Asia, and The King and the Corpse. But Zimmer was fated to never make a trip to India, in something he shared with another great Indologist Max Mueller. Zimmer tried thrice to travel to India. In the 1920s, the company with which he had booked his passage went bankrupt. He made a second attempt in 1935, but the plan failed because the German government refused him permission as his wife was half-Jewish. The last attempt he made was in 1938-39 but the tensions before the outbreak of the Second World War prevented this.

Zimmer was overjoyed to hear that Jung was to make a short trip to India in 1938. Zimmer was keen that Jung should visit the sage of Tiruvannamalai, Shri Ramana Maharshi. In the sage, Zimmer saw the true avatar of the rishi, seer and philosopher, which strides as legendary as it is historical, down the centuries and the ages. One of Zimmer’s last works was the translation of some of Ramana Maharshi’s English writings into German. Zimmer wrote, “Shri Ramana’s thoughts are beautiful to read. What one finds here is purest India, the breath of eternity.”

But Jung was unable to visit Ramana Maharshi. Maybe the dysentry that laid him low in Calcutta contributed. Jung was to later write on the sage. “For the fact is, I doubt his uniqueness. He is of a type that was, and will be. I saw him all over India. He is genuine and on top of that, he is a phenomenon, which seen through European eyes has claims to uniqueness. But in India, he is merely the whitest spot on a white surface.”

For Zimmer, writing on India shortly before his death, “Imagining India, its dense, deep fragrance in my nostrils, the jungle like an ocean before me, unknown, perhaps unknowable.” What would he have made of India had he made it to her shores? His wife wrote, “He could accept so much. It is hard to imagine he would turn away from his beloved India as he found it.”

The writer is a senior publishing industry professional who has worked with OUP and is now a senior consultant with Ratna Sagar Books