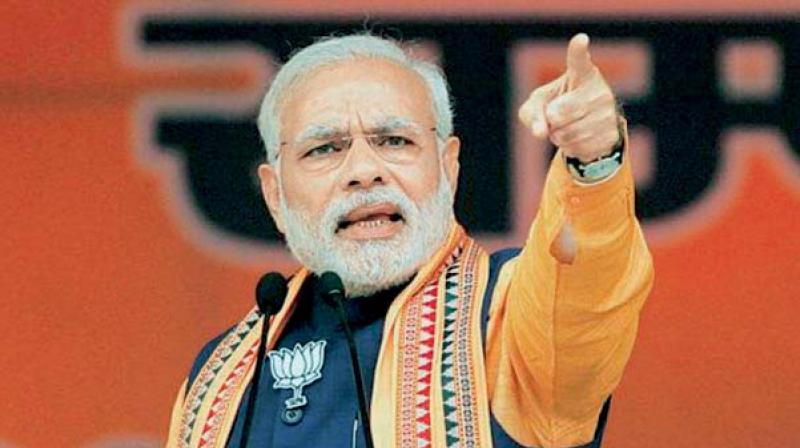

Maldives & Sri Lanka: PM starts with a bang

The presence of the Indian Prime Minister thus sends a strong signal of Indian solidarity with democratic forces in the Maldives. F

Prime Minister Narendra Modi travels abroad immediately after beginning his second term. He flies to the Maldives on Saturday, and then to Sri Lanka, focusing on maritime neighbourhood ties after hosting at his May 30 swearing-in seven Bimstec members, five Saarc countries plus Myanmar and Thailand from Asean, all from the Bay of Bengal region. The wider objective may have been to deliver a calculated snub to Pakistan, but leaving the door ajar for possible engagement. Early signs of this are already visible before Prime Ministers Narendra Modi and Imran Khan cross paths by mid-June at Bishkek in Kyrgystan, at the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit, despite denials. Sohail Mahmood, the former Pakistani high commissioner in New Delhi and current foreign secretary, was celebrating Id-ul-Fitr at Old Delhi’s historic Jama Masjid, ostensibly to accompany his family back home as his children had stayed on in India to finish school year. Only the extremely naïve will believe there was no contact with him

to discuss a possible de-escalation and re-engagement.

Prime Minister Modi has chosen the Maldives and Sri Lanka with strategic astuteness. While the scene in the Maldives had already shifted when pro-China President Yameen Abdul Gayoom, who subverted constitutionalism and the rule of law, was defeated by Ibrahim Mohamed Solih in September 2018, the elections to the Majlis (parliament) were held on April 26. The new President’s Maldives Democratic Party (MDP) won 65 out of the 87 seats up for election (the total being 88). Former President Mohamed Nasheed, who lost power in 2012 under dubious circumstances and had been in exile, returned to win a seat and become Speaker. Considered the most pro-India of all Maldivian politicians, he had the Majlis pass a resolution inviting Narendra Modi to address them. In the Maldives, this prerogative lies with the Majlis and not the government.

The presence of the Indian Prime Minister thus sends a strong signal of Indian solidarity with democratic forces in the Maldives. Further, it reinforces the Maldives’ President’s public message that while the island nation’s friendship with China will continue, it espouses an “India First” approach. This also recognises the Chinese challenge in India’s periphery and the long game India can play to counter it. India already announced, when erstwhile external affairs minister Sushma Swaraj visited the Maldives, infrastructure development aid of $1.4 billion. Now Mr Modi carries another bouquet of projects, including a cricket stadium. To displace China’s chequebook diplomacy is in order, positing India’s benign development assistance against the Chinese debt-bubble causing approach.

The Maldives may not yet have returned to complete political stability. Speaker Nasheed gets control over the Judicial Services Commission, which regulates the Supreme Court, an institution that in the past had subverted constitutionalism. Mr Nasheed also seems to nurse an ambition to regain control of the executive. Mr Modi may have to mediate to keep the MDP leaders from quarrelling over offices. China would otherwise exploit their differences to get its protégés back in power.

Sri Lanka provides an entirely different challenge, although the China factor is common with the Maldives. Political instability prevailed last year as President Maithripala Sirirsena jousted with his Prime Minister while promoting former President and rival Mahinda Rajapaksa. Simmering communal tension was ignored, despite the rioting in Muslim areas in 2018. In April, the Easter Day church bombings set the tinderbox aflame. Despite communal tension being basically between the Muslim minority, numbering nearly 10 per cent of the population, and the 70 per cent-strong Sinhala majority, the small Christian community became the target as the global Islamic jihad, in the form of ISIS recently uprooted from Syria-Iraq, burst forth in a revenge attack, perhaps for the wanton killing of Muslims in New Zealand’s mosques.

On the 10th anniversary, in May, of the elimination of the Tamil Tigers (LTTE), Sri Lanka stands destabilised by this new Muslim-Sinhala standoff. One Buddhist cleric sat on a fast-unto-death to seek firing of some Muslim ministers, allegedly for complicity in the terror attack, of which there is yet no evidence. A more militant cleric, G.A. Gnanasara Thero, recently pardoned by the President and freed from jail (which might sound familiar to Indian ears), led mobs to demand action. Nine ministers and two provincial governors, all Muslims, resigned to douse Sinhalese anger.

Not surprisingly, Mr Modi’s victory invited joy in Sri Lanka due to his strong stance against terrorism. President Sirisena, in New Delhi for Mr Modi’s swearing-in, brought four ministers, including two Tamil politicians. Separately, a Tamil politician was quoted as saying: “Yesterday us, today you, tomorrow a new other.”

President Sirisena won with the massive support of Muslim and Tamil voters. The beneficiary of this communal toxicity will be ex-President Rajapaksa. The Sinhalese may be more amenable to his message, including the pro-China group aligned with Mr Rajapaksa. But Mr Modi cannot ignore the Tamil dimension.

The fuelling of Sinhala-majoritarian sentiments will make all minority communities insecure. Mr Modi’s message will be closely watched by all communities. He has a great opportunity to rise above his tendency to view terrorism as merely a law and order issue. He must speak like a statesman, as counter-terrorism works only when good policing is supplemented by a minds-and-hearts approach. His message will be heard across South Asia and beyond, but above all Sri Lanka needs it now. More significantly, it will be heard in Jammu and Kashmir.

Preceding Mr Modi, US assistant secretary of state for political-military affairs R. Clarke Cooper swung through Sri Lanka to finalise a new set of agreements for military interoperability. India has welcomed the US’ Indo-Pacific military thrust. But for India, the challenge is an existential one — an assertive China, the Sino-US trade war, a demanding and transactional US, a recalcitrant Pakistan, radical Islam and creaking global governance structures. Mr Modi next heads to the SCO summit and the extremely important G-20 conclave in Japan. India needs an independent maritime neighbourhood strategy. It can overlap with the US approach or diverge, based on India’s supreme interests. For instance, the Andamans, Sri Lanka, Mauritius and Maldives are India’s first island chain.

That is where India’s forward defence must be centred, with or without friendly maritime powers like Australia, France, Britain and the United States. Beyond that can be layers of other initiatives like SAGAR, resting on the larger Indian Ocean Rim Association. Mr Modi’s inaugural second-term visit underscores it.