Beyond atmospherics: Populism' challenges

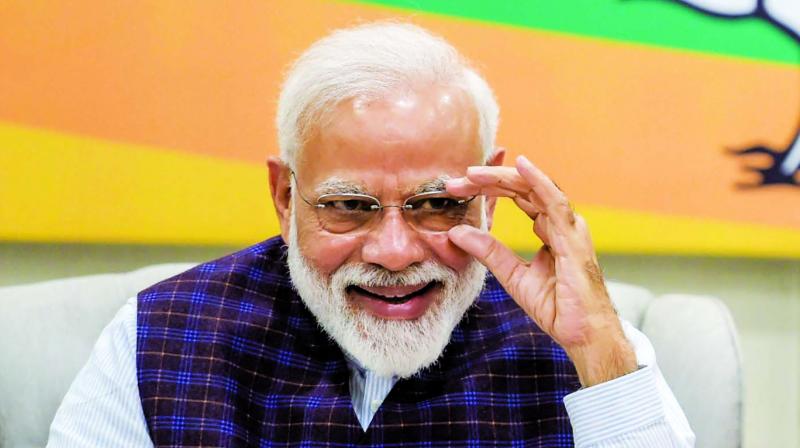

As the 2019 Lok Sabha election winds its way to a close, major political leaders appear to be unflagging in their zeal to tell their side of the story. In this election, there seem to be just two top leaders — the BJP’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who is seeking a second term, and Congress president Rahul Gandhi, the challenger, but also not really in the prime ministerial race for more reasons than one. Mr Modi shows himself to be an able politician, who rakes up issues, relevant or irrelevant, serious or frivolous, and his critics find themselves catching on to everything he says and nailing him for what he said and what he didn’t say. The man who seems to enjoy the spectacle of his critics attacking him ineffectively from all sides. Mr Gandhi, on the other hand, has in the past few weeks constructed a counter-narrative of the good man, who will fight hard against an opponent but he will not let rancour fill his soul. The essence of his refrain is that he will return Mr Modi’s “hatred” with “love”. This is the atmospherics of this election.

The underlying issues are quite different. The critics have tried to show Mr Modi, the BJP and by implication its parent body, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, as anti-minority, and especially as anti-Muslim. Mr Modi and his party do not confirm or deny the position. In his latest interview to the Indian Express, Mr Modi has reiterated the old BJP argument that the anti-Muslim image of Mr Modi and that of his party was created by the Congress, and that they — Mr Modi and the BJP — are not obliged to clear the air. It is indeed a cunning position to take, but it is a position that cannot be faulted except on sentimental grounds. That is why even the Congress Party and Mr Gandhi are not harping on the issue of minorities, and they are skirting the question whether the identity of Muslims in India is under threat. The fact is that the BJP recognises that it cannot threaten Muslims in any way even as it stubbornly refuses to humour Muslims. The clash of visions then is no more between secularism and communalism.

India remains a defiantly multi-religious society and the BJP recognises that it cannot do anything about it.

The misuse of institutions — the Supreme Court, the Election Commission, Parliament, the Constitution — is really an old issue, and these are charges that the Opposition of the time had made against the Congress when it (Congress) was in power.

Parties in power do not play fair, but the institutions survive the onslaught because the Indian constitutional system has shown itself to be fairly resilient. In different ways, Mr Modi and Mr Gandhi declare that the poor in the country need to be helped. It is interesting that though that Mr Modi still uses the old-fashioned Congress term, “the poor”, and he uses the old Congress rhetoric of “government stretching its hand to help the poor”, Mr Gandhi speaks of the unemployed youth and distressed farmers. Mr Modi’s “welfare state” differs very little from that of the old, unreformed Congress.

The real difference between Mr Modi and Mr Gandhi is Mr Modi’s compulsive populist rhetoric, and he believes, and there is an element of cynicism as well as self-delusion, that the way to win over people is to indulge without restraint in populist theatrics. Mr Gandhi, on the other hand, is both more sensible and more sceptical about the uses of populism. In a way, Mr Gandhi is more intelligent and more modern than Mr Modi in his political perception. Mr Gandhi knows that people cannot be fooled by rhetoric, while Mr Modi thinks that people can be swept off their feet through rhetoric. Mr Modi, in his naïve belief in the powers of populism, forgets that people do not believe in rhetoric all the time. Somewhere, Mr Modi is testing the limits of people’s credulity, and he would be shocked if the people were to reject him through sheer cold reasoning.

As democracies mature, and India is no exception, leaders and parties cannot take the people for a ride. Unless Mr Modi and Mr Gandhi offer a credible programme to govern the country, they will not be accepted. Mr Gandhi’s programme is tethered to reasonableness, while Mr Modi and the BJP are carried away by their own rhetoric. The Congress, and by default Mr Gandhi, have an advantage over the relatively immature BJP and Mr Modi because of political experience. The Congress never promised the moon, not even in the heyday when Indira Gandhi coined the slogan of “garibi hatao”. If not now, perhaps later, the BJP will have to give up its flaky visions of a “New India” and a powerful India which has no connect with the real India.

The delusion that the BJP and the RSS entertain about India becoming a “vishwa guru”, or global spiritual preceptor, will be the undoing of the right-wing BJP and its populist leader, Mr Modi.

The other major lesson that Mr Modi and his party need to learn from the Congress — of course, Mr Modi should remember that the Congress is not that of the Nehru-Gandhi family alone, but that of Maulana Azad, Subhas Chandra Bose, Mahatma Gandhi, Motilal Nehru, Chittaranjan Das, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Badruddin Tyabji and Dadabhai Naoroji — is the nationalist ethos, where you feel proud about India, defend and promote its interests by carrying different sections of the country together. They have to improve their political thinking and modulate their political articulation to be able to speak for the country, whether they be in government or in Opposition.

Winning or losing an election is not so important as it is to learn to engage in democratic politics. The Congress has learned its lessons because it has tasted defeat. Mr Modi and the BJP remain vulnerable because he has not yet shown the maturity of accepting an electoral rebuff. Whether the BJP wins or loses, Prime Minister Modi and the BJP remain a problem in the nation’s politics. They have yet to prove themselves to be politically mature.