AA Edit | Data rules first step, but need more fine-tuning

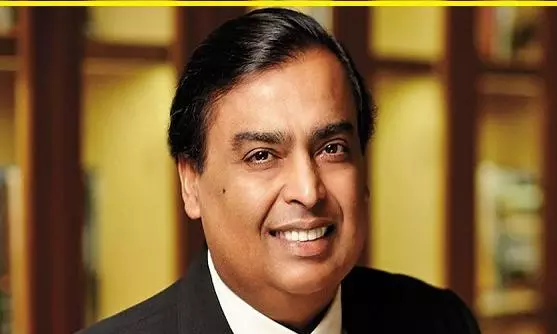

Around five years ago, Reliance Group chairman Mukesh Ambani, whose enormous wealth could be attributed to his group’s dominance in the oil refinery business, made an interesting remark: “In this new world, data is the new oil. And data is the new wealth. India’s data must be controlled and owned by Indian people and not by corporates... For India to succeed in this data-driven revolution, we will have to migrate the control and ownership of Indian data back to India.”

His remarks finally found resonance in the draft rules that the Union ministry of electronics and information technology (MeITy) notified under the Digital Personal Data Protection Act for public consultation. The central factor of these rules is consent, which means no entity could collect the user data without his knowledge and consent.

If the entities like e-commerce companies and social media companies don’t get consent of the users, they cannot collect or retain the data for any business purpose. In the event of the user denying his consent, the entities will have to erase the user data from its servers.

It is a welcome change in data governance in India, where social media companies exploit the knowledge of user’s preferences to push relevant advertisements to achieve a greater ad-to-sales conversion ratio. For instance, Google’s income from advertisements in India is Rs 31,221 crores in 2022-23 and Meta, which owns Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp, earned Rs 22,720 crores in 2023-24. Compared to over Rs 50,000-crore combined revenue of two digital ad giants, the income of the entire print media in India in 2023 was Rs 16,472.40 crores.

The current draft rules allow people to make an informed decision on whether to let a business entity use his data and for how long and for what purpose. This also creates a level playing field for businesses.

Though critics have welcomed the draft rules as work in progress, they pointed out a plethora of exemptions such as lawful conduct of data processing activities, limiting the processing of data to only that necessary for achieving specific purposes, undertaking reasonable efforts to ensure the accuracy of processed personal data and retaining personal data only as long as necessary to achieve the specified purposes or else complying with existing laws among others.

The rules are also silent about the event, where a dominant business entity makes its services conditional on the user giving his consent to share his data. In such a case, the user would be practically coerced into accepting the business entity dominance.

Unless the government bans business entities for making their services conditional on the user sharing data which is not required for the proper delivery of its service, these rules cannot achieve the desired effect. For example, an app-based messaging service should not collect the user’s food preferences as food is not relevant to its key service offering, i.e. messaging. Similarly, an online search company need not know the user’s daily travel details as its service is required only when he wants to avail its search engine and not around the clock.